Digital Social Memory and the Case of the Online Archive of Internet Art

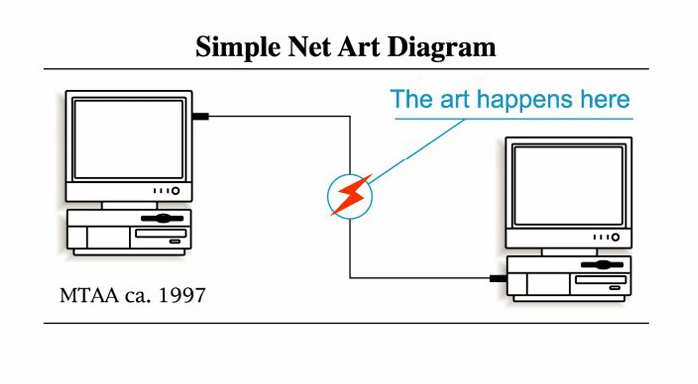

MTAA, Simple Net Art Diagram, 1997. Digital image. Courtesy the artists

Archival science and digital cultural memory

Increasingly, cultural artifacts are produced, discovered and experienced in digital environments mediated by networked devices. Cultural heritage is recorded in digital archives – the new sites of our collective memory. Access to cultural memory and knowledge is then facilitated via digital interfaces delivered through a web browser, where the dominant interaction pattern is that of search and retrieve (Whitelaw, 2015). But archives are sites of knowledge production, not simply knowledge retrieval, as theorists in the field of archival science have argued since at least the 1990s (Brothman, 1991; Cook, 2001). Under the influence of postmodernism and post-structuralism, a paradigm shift has taken place in the conception of the archive and the archival record within a range of fields including critical theory and archival science. The archival record is no longer understood to be a static entity but rather a dynamic process of production and interpretation, which is carried out by multiple agents, including the author(s), archivist(s), and the larger cultural context (Brothman, 1991; Cook, 2001; Anderson, 2013).

Despite these theoretical shifts, in practice, the interfaces of digital archives are still designed according to positivist ideas of knowledge organisation, storage and retrieval, largely ignoring the multiplicity of potential knowledge representations and interpretations. The objective role of the archivist – as a neutral facilitator for the accummulation of by-products of human activity – which has been rigorously questioned by postmodern theory (Cook, 2001), is nevertheless still projected onto the structured database. Databases and their interfaces are neither “natural”, nor “neutral” (Manovich, 2001; Hedstrom, 2002). Rather, the logic of their construction and operation has been obscured and made opaque through interaction patterns and interface design conventions. For example, chronological and alphabetical sorting orders and subject classification schemes may appear to be neutral and value-free, yet they are just one possible interpretation of knowledge representation among many other possibilities. So both the archivist and interface become intermediaries between the evidentiary status of the archive and the end user. The database/interface, can be considered as the site/s where “power is negotiated and exercised” (Hedstrom, 2002). Consciously or unconsciously, an archivist’s work determines how archival records are structured in databases, and therefore influences how their representations are accessed, used and interpreted via interfaces (Hedstrom, 2002).

In order to think through possible interfaces of digital archives which reflect the postmodern turn in archival science and move away from an “objective” position towards one allowing multiple interpretations, it is useful to focus on a specific case study.

Rhizome’s ArtBase interface ca. 2013

Rhizome and the online archive of internet art

The online archive of internet art presents multiple challenges, but also opens new possibilities for digital interface and interaction design. Internet artworks are not single, static entities, but rather assemblages of “artifacts, practices and cultural beliefs” (Dekker, 2014; Brock, 2016), contingent on the networked environment. In order to be executed and rendered, internet artworks are dependent on specific software/hardware environments, network protocols and user interactions. Both aesthetics and meaning production in internet artworks are constructed through the ensuing relationships between the constituent parts of the assemblage. Moreover these relationships are not fixed, but instead change over time. The archive of internet artwork challenges traditional archival concepts regarding the archival record itself, as well as its classification and representation.

The dynamic relationships between elements of the artwork assemblage, which may involve software applications connecting to dynamic external databases or user interactions which evolve over time, for instance, presuppose a multiplicity of possible representations. The interface design of the archive of internet artworks should therefore be able to reflect this multiplicity. What is more, the interface should be able to make visible the decisions behind certain archival representations, in order to inform potential user interpretations.

Aside from organising archival records and facilitating access to them, one of the core goals of digital archives, as defined in the Encyclopedia of Archival Science (2015) is the long-term preservation of digital records. In the case of internet art, the preservation of the artwork-assemblages, whose constituent parts are subject to the rapid cycles of technological change and obsolescence, can be particularly challenging. There are a number of organisations and institutions who have recognised this inherent vulnerability of digital cultural artifacts and have developed various strategies towards safeguarding digital cultural memory. One of the longest standing and still operational organisations is Rhizome, founded in 1996 as an online arts organisation and community-building platform. In 1999, Rhizome established the ArtBase – an online space to present and archive internet art, as well as to build a community and a discourse around the works. Since then, the ArtBase has changed its structure and interface design numerous times, while Rhizome worked towards developing various strategies for supporting public access to digital cultural memory. More recently, the organisation has focused on a few specific projects, which have the potential to redefine three core concepts for understanding the digital archive – performativity, provenance, and presentation.

Net Art Anthology, Chapter I, 2017

Performativity, provenance and presentation in the archive

If artifacts in digital archives are no longer understood to be static objects or entities, then archiving their dynamic characteristics requires enabling a representation of their performativity. In addition to the traditional archival paradigm of search and retrieval, the digital archive needs to facilitate continuous two-way interaction between a user and the digital artifact, and in the case of the Artbase – the artwork-assemblage. Preservation of cultural memory is contingent on the performativity of the artifacts in the archive.

Rhizome has recognised the significance of performativity in relation to the archive of internet art, since aesthetic form and meaning production in internet artworks are often directly dependent on user interaction. One of Rhizome’s most significant preservation projects over the past few years has been the development of Webrecorder, a web archiving tool. Its core functionality is based on the two-way exchange taking place between client and server when we are browsing the web. Webrecorder records the dynamic traffic between the user’s browser requests and the responses from the online hosting environment, thereby facilitating the archiving of online artifacts as they are encountered by the user. Webrecorder’s browser-based app also provides the infrastructure to replay, or reperform, the archived artifacts within the browser. Through these two capabilities – record and replay – Webrecorder enables the archiving and reperformance of complex and dynamic internet artworks, such as Amalia Ulman’s Instagram piece Excellences and Perfections (2014), which explores the interactions between an Instagram user and their followers. Without a tool such as Webrecorder, preserving this artwork in its original environment and presenting it via a performative archive would not have been possible.

The preservation of a contemporary work of art, such as Ulman’s piece, was also made possible by the preservation team’s understanding of the artwork’s context of creation. The preservation and reperformance of historic artworks from the archive requires an understanding of the artworks’ provenance. The traditional concept of archival provenance, however, which specifies a single place, time, and creator for the archival record, does not translate well to the context of a digital archive, whose contents are complex and dynamic assemblages. Instead there is a need for a more “elastic” concept of provenance (Cook, 2001), which can account for various dynamic functions and processes. A key concern for the backend of Rhizome’s archive remains the development of a provenance framework, which can adequately describe not only the origin of each artwork record and the transformations that may have been applied to the record, but also the dependencies for the reperformance of the artwork and the context within which a reperformance happens, a context which also includes the audience / (user) experience of the reperformance.

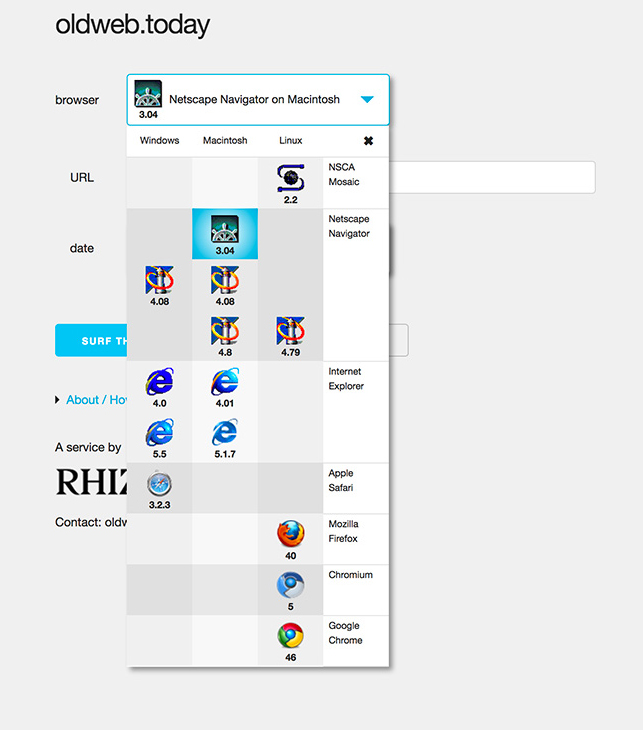

Oldweb.today interface, 2017

Oldweb.today interface, 2017

If the backend of the archive contains the expanded provenance information, then the frontend interface needs to facilitate presenting artworks in their historical context of creation. Another focus of Rhizome’s preservation programme has been the development of tools that can facilitate browser-based software emulation – both for legacy browsers (e.g. old versions of Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, or browsers from the ‘90s such as Netscape Navigator) or full system emulation (e.g. for the purpose of emulating applications running on Classic Mac OS or Windows 95 operating systems). Oldweb.today and Emulation-as-a-Service (developed with the University of Freiburg) are tools that facilitate such emulation. The legacy browsers served through the oldweb.today system, for example, allow the presentation of artworks in historically accurate environments and support obsolete plug-ins. Thereby historic artworks which otherwise no longer run in contemporary browsers, can be reperformed. This kind of software emulation, which is served within the user’s own browser, has been instrumental to successfully present numerous artworks as part of Rhizome’s ongoing online exhibition project – Net Art Anthology (2016–2018). What is more, presenting artworks in legacy environments or encapsulating them in a time-stamped archival copy via Webrecorder clearly places them within an archival framework. The constructed nature of this framework is made visible to the user in the frame of the emulated Netscape browser or Webrecorder’s navigation banner. This form of archival presentation does not claim “objectivity”, but rather introduces the user to one possible reperformance, among many, and invites interpretation.

Next steps

There has been significant progress in expanding traditional archival concepts such as provenance and in developing new preservation paradigms with consideration for the notions of performativity and presentation, both within Rhizome’s own practices and in the larger field of digital cultural heritage. Yet there are still aspects of the construction and mediation of culture through digital interfaces that remain problematic. Digital interfaces are cultural artifacts themselves – constructed through the collaborative work of designers, developers and institutional stakeholders – and therefore subject to the same issues of cultural discourse and interpretation that digital archives need to address, too. Moving beyond the search and retrieve “objective” model and towards an expanded context of representation, which allows for, and indeed encourages, multiple views and interpretations is an ongoing project within the digital humanities (Drucker, 2013) and will require concentrated efforts among both practitioners and researchers. Nevertheless, the case of the online archive of internet art and some of the tools and strategies developed by organisations such as Rhizome demonstrate possible steps towards a more versatile practice both in the field of archival science, as well as interface design.

Lozana Rossenova is a PhD candidate at the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image and her research is a collaboration between London South Bank University and Rhizome in New York.

References

Anderson, K. (2013) The Footprint and the Stepping Foot: Archival Records, Evidence, and Time. Archival Science 13 (4), pp. 349–371. DOI: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.lib.iastate.edu/10.1007/s10502-012-9193-2.

Brock, A. (2016) Critical Technocultural Discourse Analysis. New Media & Society, 1 (19). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461444816677532

Cook, T. (2001) Archival Science and Postmodernism: New Formulations for Old Concepts. Archival Science, 1 (1). pp. 3–24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435636

Dekker, A. (2014) Enabling the Future, or How to Survive FOREVER: A study of networks, processes and ambiguity in net art and the need for an expanded practice of conservation. PhD dissertation, Goldsmiths, University of London

Drucker, J. (2013) Performative Materiality and Theoretical Approaches to Interface. DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly, 7 (1). Available from: http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/7/1/000143/000143.html [Accessed 06.08.2017]

Duranti, L. and Franks, P. (2015) Encyclopedia of Archival Science. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Hedstrom, M. (2002) Archives, Memory, and Interfaces with the Past. Archival Science 2, pp. 21–43.

Manovich, L. (2001) The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Whitelaw, M. (2015) Generous Interfaces for Digital Cultural Collections. Digital Humanities Quarterly. 9 (3). Available from: http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/9/1/000205/000205.html [Accessed 3 September 2017]