YouTube Feminism: Not Medium but Métier

{category_name}I taught Learning from YouTube (LFYT) for the fifth time this year. The first iteration was in 2007, fresh into the early years of the still short life of YouTube and social media more generally. I taught the course again this semester, after a several year hiatus, because I was interested in two things: accounting for what has changed in these 8 years as well as for the confounding relations between social (in)justice and social media (which I have reflected upon twice at Lady Justice a part of New Criticals committed to “reconsidering gender and technology in the age of the distributed network”).

While the most obvious changes on YouTube are 1) its unimaginable and consistently escalating scale (seemingly as large as the world, or at least the world of media, more on this later), which itself is connected to the ever shortening time-scale of memes (see video above by LFYT student, Samantha Abernathey, one of several videos made for 2015’s Meme Project) and 2) the marked consolidations of its professional and financial infrastructures and outputs (allowing for new modes of mediamaking and their monetization that sit precociously between amateur and expert media and which actually do make people/corporations/YouTube/Google money). What I will focus on here is another glaring, although perhaps more variegated change, 3) the nature of feminism on YouTube as a way to think about the massive cultural, political, and personal shifts associated with the rapid maturation of social media. In the brief observations that follow, I will press my course (which, surprisingly [definitively?] was taken by 14 women, “feminists” all, and 2 men, probably “feminists” too; whereas in its past iterations it had been dominated by male students, often [definitively?] basketball players, probably not “feminists”) into conversation with another example of feminist media pedagogy, a memorable symposium I just attended at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan: Feminist Video Documentary Strategies in Social Dissent and Change (organized by Michigan art professor, Carol Jacobsen with Vicki Patraka and Joanne Leonard). There, in Ann Arbor, in conversation for three intense and fully-scheduled days with eleven hand-picked feminist scholars, artists, and activists, ranging from their mid-forties to mid-seventies, fully-formed, carefully-schooled, and highly - and deservedly-vetted for their diverse and stunning bodies of activist feminist documentary work, built in some cases beginning in the 1970s, and occurring all over the world and in regards to feminist issues as diverse as prison reform, domestic abuse, racism, homophobia and Chevron, and the dreams of female Indonesian domestic workers in training—an anti-YouTube if ever there was one—I encountered a feminist media space that itself put the changes at YouTube into another form of stark release.

In 2010, thinking about my teaching and writing about YouTube within my video-book about this, I suggested that my feminism, and feminism more broadly on YouTube, was closeted. With a tip of the hat to both film scholar and critic, B. Ruby Rich and feminist poet and theorist, Adrienne Rich, I attempted to create sign-posts to better mark and see the “nowheres and everywheres” of this new closet, one which I named as holding many hidden-away in plain sites for feminisms:

In 2010, thinking about my teaching and writing about YouTube within my video-book about this, I suggested that my feminism, and feminism more broadly on YouTube, was closeted. With a tip of the hat to both film scholar and critic, B. Ruby Rich and feminist poet and theorist, Adrienne Rich, I attempted to create sign-posts to better mark and see the “nowheres and everywheres” of this new closet, one which I named as holding many hidden-away in plain sites for feminisms:

- ARCHITECTURAL or ARCHAIC feminism occurs at a deep and structural level

- UN-NAMED feminism that in so doing sees itself newly

- MORPHING feminism transforms to encapsulate other beliefs in feminism’s name

- FRAMING feminism that umbrellas the social justice work of trans, anti-war, anti-racism and other activisms

- ASSERTIVE or INSERTIVE feminism that names its relevance in places where it wasn’t deemed important

- COMMON-CULTURAL feminism that assumes feminism is the shared space of production

- ACCESS feminism that doesn’t only speak to feminists and also speaks to feminists by opening access to unusual places

- TECHNO feminism that engages in collaborative, goal-oriented, placed, critical self-expression online

- ASSUMPTIONAL or PRESUMPTIVE feminism that always assumes that feminism counts and that feminists speak

While these terms sign-post places that are still very much alive and operational on YouTube, what I had not mapped then is how YouTube, like the world itself, a world itself, and as one of the places that makes our world itself, now also, at the same time, holds unimaginable quantities of visible, uncloseted, never-closeted feminisms:

- OVERT feminism that names itself proudly and often attached to equally proud descriptors (i.e. Black, trans, queer)

- TRENDY feminism that attaches to memes, celebrities, and products

- WARRING feminism that pits feminists against each other

- TWITTER and TUMBLER and INSTAGRAM and PINTERST feminisms that spread, link and grow transmedially

- TROLLING (against) feminism that harasses, stalks, demeans, threatens, bullies and endangers

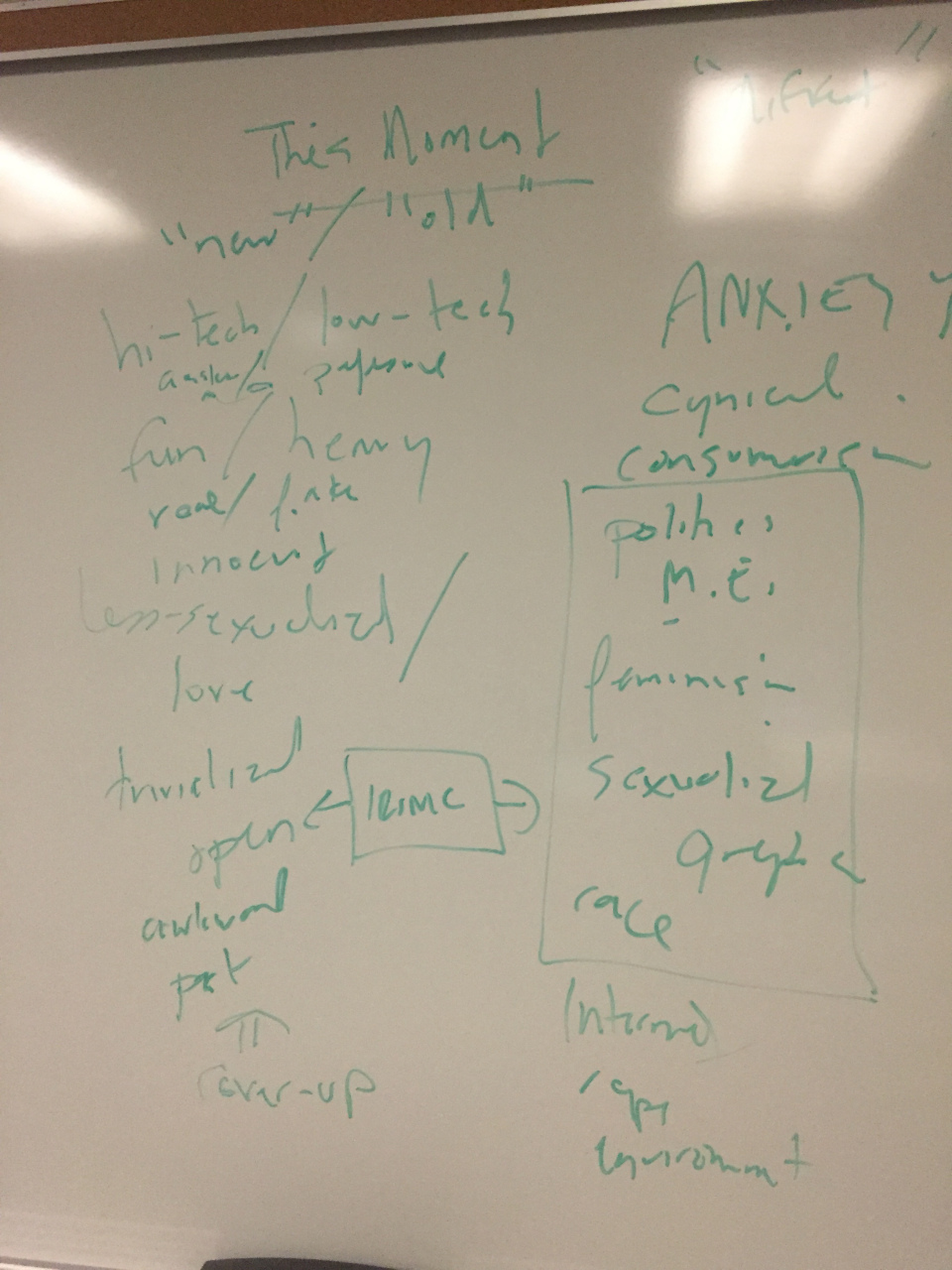

YouTube is truly a (corporate) space where everything and everybody is (with notable blind spots both self-chosen and socially deployed). As proved true for the feminist demographic and associated conversations within my 2015 class, YouTube has become a place of, for and by feminists and this overt engagement has brought clarity and confusion. My students, like all of us who are engaged with social media, name an anxiety, cynicism, and consumerism that is core to their new media experience even when they are being “political” (in the production, or more definitively consumption of overtly “feminist” media) but especially when they are not, when they are taking a much-deserved break from the onslaught of “feminism” that now greets them there and so are watching the innocent, fun, funny, trivial (corporate) content that surrounds the feminist media also readily-available.

Meanwhile, the Michigan feminists also attested to a level of fatigue, anxiety, and hard-to-manage overwhelmedness brought on by new and social media consumption practices. I suggested that media production and its feeding feminist process, now radically accessible to so many, is a final feminist frontier in that it can maintain attention, ethical conditions, non-corporate environments, and clearer boundaries of commitment that now seem nearly impossible in the space of new media reception given the noise, hyper-visibility, and corporate domination of this space. As you see, these conversations circled around architectural metaphors and material considerations attempting to describe possible feminist media spaces, norms, and histories that might be defined by counter-, concordant-, and/or immersive YouTube practices (a project I have being pursuing in my Feminist Online Spaces work).

Meanwhile, the Michigan feminists also attested to a level of fatigue, anxiety, and hard-to-manage overwhelmedness brought on by new and social media consumption practices. I suggested that media production and its feeding feminist process, now radically accessible to so many, is a final feminist frontier in that it can maintain attention, ethical conditions, non-corporate environments, and clearer boundaries of commitment that now seem nearly impossible in the space of new media reception given the noise, hyper-visibility, and corporate domination of this space. As you see, these conversations circled around architectural metaphors and material considerations attempting to describe possible feminist media spaces, norms, and histories that might be defined by counter-, concordant-, and/or immersive YouTube practices (a project I have being pursuing in my Feminist Online Spaces work).

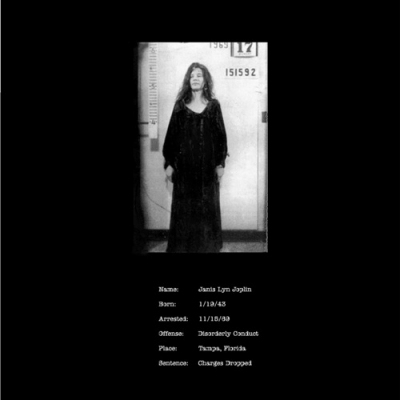

The twenty-five year plus bodies of work shared by many of our group who have devoted their careers to ongoing, careful, connected, personal and political media projects help refine vocabularies for feminist media practices that can and do share the broader media ecology with YouTube and social media. For instance, our host, Carol Jacobsen, has been making photo and video for over twenty-five years as part of her work as the Coordinator of the Michigan Women’s Clemency Project, advocating for the human rights of women prisoners and seeking freedom for women wrongly incarcerated. Her feminist media work has been shown in galleries, used by activists, lawyers and policy people, and contributed to the release of nine wrongfully-incarcerated women. Some of it is on Vimeo while also sitting elsewhere across the Internet.

I would like to conclude by thinking through the experiences in Michigan (where we sat for two-plus days in an isolated, quiet, and window-less conference room while each participant took an hour or more to present her work, and we listened and responded with heightened focus) as a way to also see some of the notable dark spots that are by definition lost to the eye within our (new) place of feminist hyper and over-visibility. Critically, these eleven women were significantly older than your typical “YouTube feminist.” Each had an institutional home that she may have fought to achieve over most of her career, that she had made herself by creating this counter-institution on her own or with others, or that she was precariously connected to or even retiring from. But notably, the diverse feminist media activism of this group shares certain core values, practices, and infrastructures quite different from the ones I have mapped through YouTube thus far, ones which signal time, space, connection and attention as core:

I would like to conclude by thinking through the experiences in Michigan (where we sat for two-plus days in an isolated, quiet, and window-less conference room while each participant took an hour or more to present her work, and we listened and responded with heightened focus) as a way to also see some of the notable dark spots that are by definition lost to the eye within our (new) place of feminist hyper and over-visibility. Critically, these eleven women were significantly older than your typical “YouTube feminist.” Each had an institutional home that she may have fought to achieve over most of her career, that she had made herself by creating this counter-institution on her own or with others, or that she was precariously connected to or even retiring from. But notably, the diverse feminist media activism of this group shares certain core values, practices, and infrastructures quite different from the ones I have mapped through YouTube thus far, ones which signal time, space, connection and attention as core:

- SEQUESTERED feminism where the environment to share the work is small, closed, respectful, and supportive.

- SLOW feminism during which we took time, were not rushed, and no one multitasked; we listened, watched and were focused (thanks to Meena Nanji for this term and the previous one).

- RESEARCH feminism where work is anchored in (often) funded and mostly multi-year engagements

- AESTHETIC feminism where the refinement of a personal practice takes place in conversation with other artists and traditions

- HISTORIC feminism that knows and marks where it comes from

- PLACED feminism grounded in and connected to a lived or political community

- VERSIONED feminism occurring over time and in conversation with other work, changing audiences, and history

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve already suggested that everything and everybody is on YouTube, which by definition puts all of these women, their methods, and projects there, too (or not if they inhabit the dark space by choice or exclusion).

Furthermore, a significant subset of “Hashtag” or “Twitter” feminism functions quite similarly to what I have named above. Lisa Nakamura’s recent work on This Bridge Called my Back on Tumblr being only one of innumerable examples of such practices. I am not suggesting that social media can’t or doesn’t attend to architectural, historic, or sustaining feminisms. Rather, I am curious about how these many feminist modalities map onto or next to each other, how they feed or frustrate us, how we can build experiences and media for feminisms with intentionality and purpose given the conflicting norms of the many media spaces that are now available to us. Thus, the current state of YouTube feminism is not a matter of medium (or age or even institution) and entirely one of métier: taking the time, making the space, producing the architecture, community, and history from which to make, receive, and relish our very best work.