Till Human Voices Wake Us

{category_name}An article in the October 28th issue of The New Yorker warns about the dangers of “presentism,” the fear that while technology continues to infiltrate many aspects of everyday life, we begin to forget about everything that is not ultra-present. But email, which is automatically archived, keeps the past incredibly accessible. The only criteria for something to be archived is that it occurred. This creates a type of memory that is at odds with the common concept of history, which says that only traditionally important things are recorded and remembered. In high school, you are taught an abbreviated and predetermined history—a set list of wars, presidencies, and laws. We only remember what we are told is important.

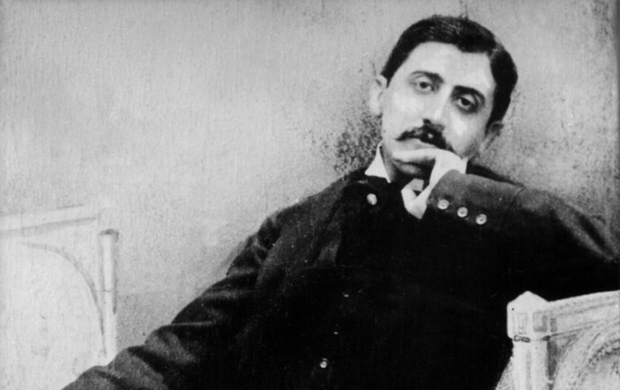

Involuntary memory refers to memories triggered by daily events (getting the mail, tying your shoelace, biting into a peach, etc.). This, unlike other kinds of memory, is not conscious or intentional. These moments are unexpected. Think of Proust’s narrator in Remembrance of Things Past. He dips a piece of cake into his tea, and this single motion resurrects memories of similar experiences, as well as a myriad of other past moments. He expresses the feeling as “an exquisite pleasure...something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin…[an] all-powerful joy.” Then he asks: “Whence did it come? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it?” (1) For the narrator, this was a singular moment—a parenthetical that had a beginning and an end.

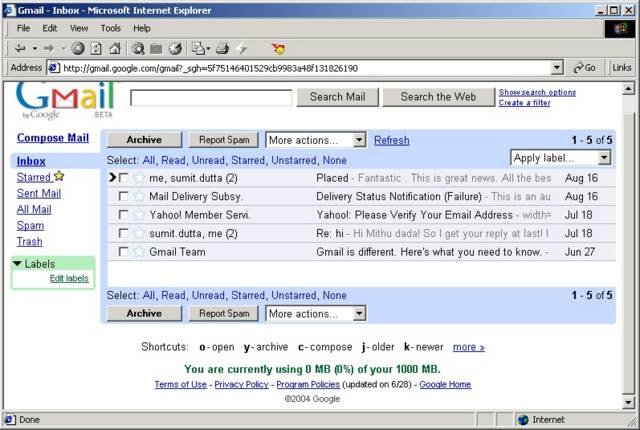

For Proust’s narrator to experience involuntary memory, he had to be in a certain place (at his mother’s house), doing a certain thing (dipping a madeline into his tea). Now, all we need is an Internet connection. This type of experience is infinitely capable of happening—maybe twice a week or three times per day or even once every few hours. I recently typed “BAM” into my gmail search box to try to find the ID number for my Brooklyn Academy of Music membership. I found my ID, but I also found an array of chats and emails that all contained this keyword, which was irrelevant to my membership. As one reads, “then a few months later: bam!” another, “bam! she appeared.” It was disorienting to be confronted with this disperse collection of emails. I was forced into these memories of past moments. (What happened a few months later? Who appeared?)

Since 2007, gmail has been recording everything. No one asked for these records, yet they exist. I can read the first email I ever wrote and remember how I sat when I wrote it (legs crossed), what I wore (gray sweatshirt, running shorts), the way the room felt around me (Brooklyn sublet—clean and foreign). I can then scan a few years forward and remember moving cities and changing jobs. I can remember breakups and breakdowns. And now, especially because email has become so ubiquitous in both our work and personal lives, there are records of nearly every emotion—no matter how dull. Unless there is a technological revolution, I will likely have this same gmail account for the rest of my life—meaning—fifty years from now, I will be able to recall what it felt like to write this article. Words and memories and emotions become hard data.

Memories are emotional. They force you to revisit parts of the past that may have been previously forgotten or (purposely) ignored. They make you accountable to yourself. A child is happy precisely because he does not carry around the weight of such memories. Children are able to avoid involuntary memory because they have a vastly different relationship to remembering. Everything they do, they do for the first time. There is no connection between one occurrence and the next. As people age and gain experiences, they lose the ability to disconnect from the past. The possibility of living without memories becomes increasing more difficult, if not impossible.

Now, not even death ends memory. Gmail has a setting where, upon your death (or your disappearance from the Internet), your password and documents will be sent to your chosen recipient. Even when you die, your memories (as opposed to the memory of you) lives on. Hannah Arendt described history’s task as “saving human deeds from the futility that comes from oblivion.” [2] These past deeds were memorialized in epic poems, songs, and oral traditions—you could only preserve a purposeful story. Involuntary memory removes this narrative structure. My search results are just computer-generated—they have no soul, no context. And when I’m gone, you'll remember me by my subject lines.

[1] Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past, Volume 1, Swann’s Way: Within a Budding Grove, trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin (New York: Vintage 1913-27), pp. 48-51.

[2] Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought, (New York: Penguin Books 1977), p. 41.

Thumbnail image by Jordan Yearsley.