The Nature of (Southern) Gothic

Pardon me while I allow my curmudgeon to speak, briefly. I find there are few more odious sentiments than “some things are better not to think about,” which is, at heart, a preference for the comfortable over the true. As though obliviousness might make the trouble go away. I’ve heard iterations of the phrase several times over the last few weeks, and it always rings false in conversation, a deferral dressed in politeness.

Perhaps my argument is with the whole military-industrial cliché complex, churning out major network ready tidbits of shallow wisdom the sponsors can match with glib, friendly-sounding taglines. The kinds of taglines that tell you, in tones appropriately Draperian, Don’t Worry, Buy Happy. And yet, what is this lingering doubt that remains? What dissatisfaction still chokes with gall the sweetness we were meant to savor?

The complaint might grow into a multiplex fret, but the ground I want to work is actually quite small. You see, I am (fortunately or unfortunately) a passionate defender of the ways literature teaches us how to live and be, not just with ourselves, but also with each other. Hence, the straw man above who says, “there are some things it’s better not to think about,” who expresses a sentimental view, and would prefer to avoid pain and violence, to the point of denying these things exist. He also would not read the kinds of works that deal with any ambiguity (moral or otherwise), or the uncertainty and doubt ever creeping in. Our very cooperative straw man, then, would not enjoy reading Southern Gothic literature.

To name a few, there is the literature of marvelous bewilderment (Italo Calvino, Angela Carter), the literature of the infinite self (James Joyce, Marcel Proust), and there is the literature of wildness and fear, the Southern Gothic, as practiced by Flannery O’Connor and Cormac McCarthy. A preference among these is not nearly as important as an understanding.

First: I think of John Ruskin, who wrote about the development of the Gothic aesthetic in architecture, and praised the barbarousness in its character, the wildness that gave the style its name. The appellation Gothic was meant, in the Renaissance, as a deprecating assessment of its darkness and brutality. Yet it had become, by the nineteenth century, a denotation of alluring weirdness. Notre-Dame, or closer to home, St John the Divine, have the hallmarks of the style: stone-ribbed vaults, supported by huge columns and flying buttresses, and walls almost entirely set in stained glass.

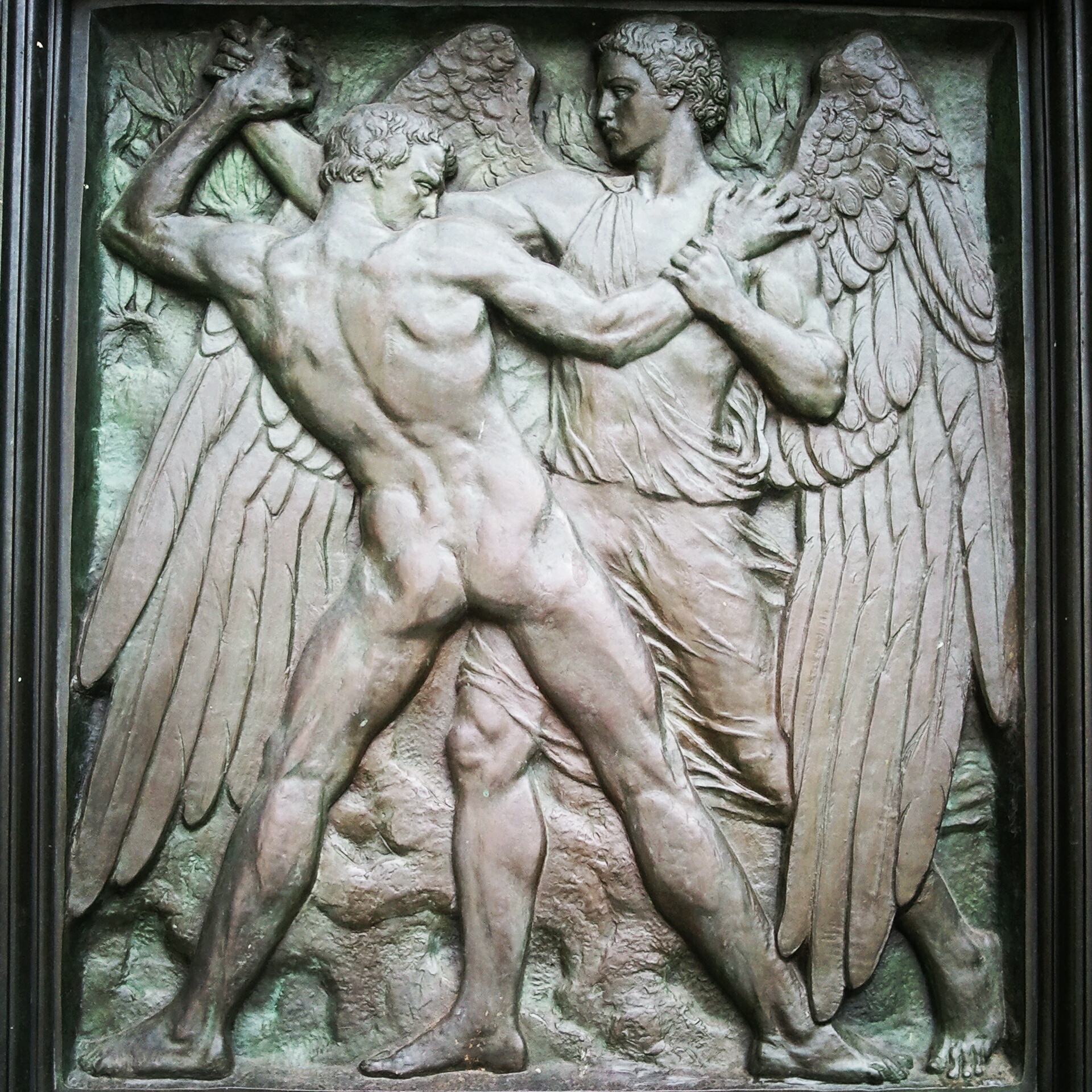

Notre-Dame’s main portal contains a stonecarved scene of Christ enthroned, surrounded by angels and saints. Just below his feet stands the everlasting figure of human vanity, Satan, with scales in hand, weighing mortal sins and taking the unrepentant away to hell. The Gothic, for all the holy glow of light and metaphors for Christ’s redemption of the world, does not consign the fouler things to go unseen. Death, naturally, but sin as well, in the form of grotesques, demons and impossible beasts, stand ever ready to remind the poor parishioner of the fragility of salvation.

In a de-christianized context, the gruesomeness can seem out of place in any art; with salvation and damnation made academic, the ghoulish apparitions hanging from the pinnacles of bell towers seem mere remnants of an older, less enlightened order, before civilization rounded off the edges. In an age of woefully obvious CGI, no howling beast can cross the uncanny valley to threaten us in our sleep.

Thus: architecture may challenge the viewer, but will never discomfit the viewer. The grotesque lives elsewhere now, in a different city altogether, in literary rather than plastic arts. The grotesque can often be found in literature as the macabre, the ecstatic description of gore and death. Both O’Connor and McCarthy tread that ground in their novels, populated with ne’er-do-wells and wanderers searching in the American South for something they can’t put words to, which they often fail to find. Hazel Motes in O’Connor’s Wise Blood and Cornelius Suttree in McCarthy’s Suttree are two such unmade men, willfully failing to participate in the ruse of society and embracing a primal foolishness. These are men against: against something they both do not and refuse to understand.

Motes in Wise Blood rails against Christ, and wishes to be a prophet against God, the paradox of an atheist charismatic lost on him. The eponymous Suttree rebels against privilege, becoming a drunk subsistence fisherman for the purity of rebellion. Because an awful history burdens the South, so it must burden these characters, too, in the form of accepting poverty, the profoundest form of violence. The search becomes a quest for any kind of meaning, and both learn through violence, Suttree through the deaths of his comrades in privation, Motes through acceptance of suffering, ridicule, blindness, and death.

What ties these characters to the demonic carvings on cathedrals is the awe the viewer feels in the presence of such strangeness. Here we encounter suffering as plain fact, even without the catharsis of tragedy; no succor comforts these men, who walk among the living like specters of warning, souls without rest and lives collapsed in violence. Motes and Suttree strive with the world, wrestling against even the necessities of survival, without fully comprehending the reason for their struggle. Tracing any kind of motivation becomes a fool's errand, as each character defies the readerly tendency to identification and sympathy.

Neither McCarthy nor O'Connor shy from horrific depiction; both write their characters in difficult lives, witness and party to appalling acts. Because in this particular kind of novel, the animal does not merely linger in the corners of the cerebral, it displaces it; simple biological impulse and action—instinct—manifests itself in the places where civilization will not go, where men and women suffer at the hands of the civilized. These are writers whose subject is the person who my convenient straw man passes by without seeing, he who will not give change to them because they will squander it. Because some things are better not to think about.