That’s Infotainment! Virtual Pedagogy and Instagram Populism in the Museum

{category_name}

Dorothy Howard and Felix Bernstein are artists who straddle the line between museum and academic work (performances, lectures, classes) and biting critique. Howard has been recently producing online zines and doing workshops in museums and libraries and Bernstein’s most recent performance at the Whitney museum worked with and against queer pop themes. Here, they chart a symptomatology of contemporary pressures and limitations around the use of social media, digital labor, performative partying, and queer fashion in museums. Showing that one way to confront art’s seasonal expectations is to acutely analyze its myopic particulars.

Dorothy Howard and Felix Bernstein are artists who straddle the line between museum and academic work (performances, lectures, classes) and biting critique. Howard has been recently producing online zines and doing workshops in museums and libraries and Bernstein’s most recent performance at the Whitney museum worked with and against queer pop themes. Here, they chart a symptomatology of contemporary pressures and limitations around the use of social media, digital labor, performative partying, and queer fashion in museums. Showing that one way to confront art’s seasonal expectations is to acutely analyze its myopic particulars.

The rise to prominence of hybrid and online learning in museum education departments is the latest attempt to delay decreased relevance in the digital age--and to furnish what Boris Groys calls the institution’s common project: resisting “material destruction and historical oblivion.” Education departments are good for public image. Such programming tempers the assumed institutional elitism of Haute bourgeois spectators and critics and corporate sponsorship appears tempered. But the progressive educational tech-savvy have added new charisma to the museum; enter new curatorial styles that utilize crowdsourcing and Instagram #selfie populism, key tactics to produce blockbuster shows that emphasize democratized access to a newly interactive, queer, hybrid, art space. Trouble is, when you aestheticize community behind fashionably closed doors, you run into the commerce and hierarchies that come from the gap between the promises of a “world wide” web of inclusion.

“Museums have experienced a real paradigm shift in that the core functional model of a museum has expanded to incorporate publishing and broadcast as well as locative experience,” says cultural information specialist Nick Poole on the public Museum Computer Network listserv. Echoing for-profit online universities, museum courseware has the remedial goal of “filling in the gaps” of public education—making the case for art’s utility as an interdisciplinary field that can co-exist with STEM education and digital humanities lessons; see the MoMA Courses Online / MoMA on Demand.” The description of an recent Coursera course, co-led by Duke professor Pedro Lasch, and Creative Time curator Nato Thompson asks: “Can a MOOC be a work of art?” promising to take advantage of the global Massive Open Online Course. Museums are only a small peg in a new industry of cultural educational technology. For-profit online degrees and open source learning are becoming a standard part of the Western educational landscape; at the very same time that funding is being slashed for the humanities and arts communities.

Stedelijk Museum. 1960.

Behind the public image is the private system—didactic digital media populism ensures links to the federal grants systems and technocratic funders. A not so secret secret, since biennials and triennials increasingly function as showrooms for emerging startup technologies and fashion brands. Given all the protests against gentrification, museum expansionism, and unfair labor laws one wonders how and why academically sanctioned institutional critique has yet to tackle the post-Internet landscape of art.

“Institutional Critique,” namely the neo-Frankfurt School methodologies of the 70s and 80s that crystallized into the Whitney Independent Study Program, has long served as a check against politically naïve shows, where the critical artist received exemption from their art-market position.The Whitney ISP model, which churns out new artists and curators, who read Capital and Hal Foster (perhaps, or perhaps not, to fit in) museum education departments will hold seminars that invite a select group of people to study institutional critique and theory, which leads to curated events that serve as illustrations of the readings. Since this new landscape of digital education departments borrows its stylistics from the ISP model, as well as feminist and queer, radical critiques issued without academic sanction; it becomes that much harder to critique than the “old guard” of museums.

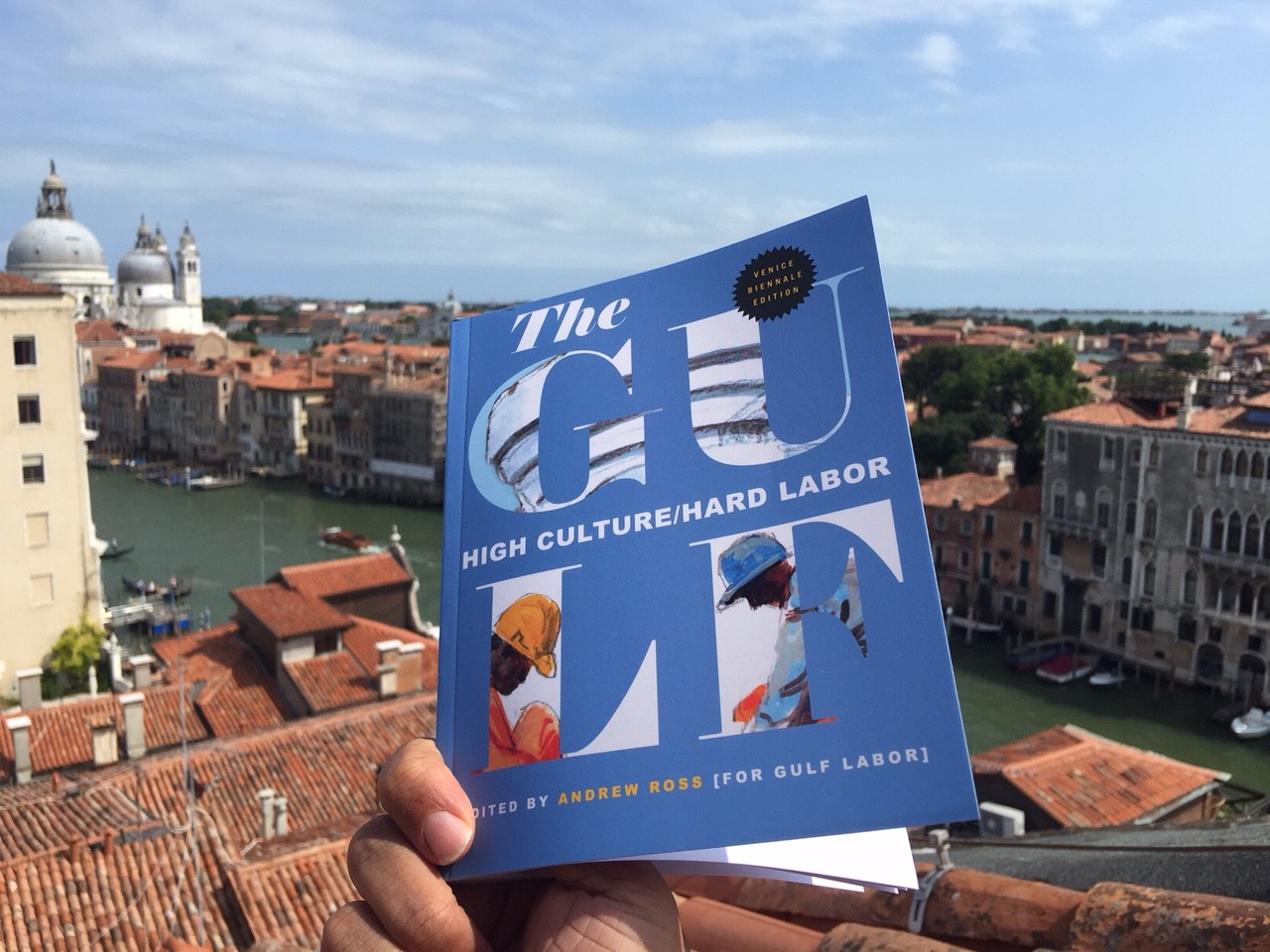

GULF Labor action at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. February 22, 2014

Take, for instance, the rise of the “art-as-education” annex, such as Triple Canopy’s EXPO 1 School in New York, MoMA PS1’s architectural dome environment hosted in May–July 2013, an experiment in an institutionally-funded classroom collaboration, and related museum affiliated art programs such as Campus der Künste. These annexes have little in common with the ideal of communal aesthetic politics of Black Mountain or the CalArts Feminist Art Program, but do echo the top-down factory model of Joseph Beuys, who organized his “commune” of students under the umbrella of his charismatic avant-garde authority brand.

Today’s charismatic impresarios, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Klaus Biesenbach accelerate and globalize his utopianism to dystopic scales. At best, these curators are tongue in cheek, but at worst, they amalgamate “art products” without compensation. Meanwhile, the corporatizing art-world subsumes theory-based-activism-as-art, exemplified by the Gulf Labor Artist Coalition, a protest against the labor practices in the UAE in the building projects of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and The Louvre Abu Dhabi, and other branded museum developments on Saudi Arabia’s Saadiyat Island. At the jet-set 56th Venice Biennale, GULF read a statement, released its 2015 report, and altered and moved the Gulf Labor Coalition banner to the Israeli pavilion– a self-called 'intervention,' which registers as spectacle of the activist group as political propaganda, ambiguously endorsed as a political stance by the Biennale, but nonetheless showcased at one of the year's most high brow mega-art events. Didactic PowerPoints and interdisciplinary debates are necessary components of contemporary art practice, à la Amalia Ulman’s June 2014 Swiss Institute conversation with plastic surgeon Dr. Fredric Brandt. These interdisciplinary artist panels bring the artist-as-instructor into the museum mainstream.

Yet in catering to the lack in public education, art institutions have used pedagogical crowdsourcing to mask outsourcing volunteer labor and used the sharing economy to conceal the visitor’s continued role as passive-consumer. Hack-a-thons and remedial workshops have become an “urgent,” multi-departmental, curatorial projects at the museum. Media studies writer Lily Irani writes of “Hack-a-thons and the Making of Entrepreneurial Citizenship,” explicating the way cultural representation has become a commodity, a hobby of the leisured knowledge-labor class civically hacking culture. Institutional hack-a-thons like the Met Museum’s 3D Hackathon, organized with staff from MakerBot Industries, or the American Museum of Natural History’s overnight ‘Hack the Universe’ event, could be read as isolated examples of new curatorial practices targeting the technologically minded, but also as deliberate targeting of the MacBook Air-wielding techno-elite that represents a significant new funding field. In a world where entering a CAPTCHA, and other types of challenge-response tests are designed to tell humans and computers apart also constitute digitized texts transcription projects, institutions have a strong interest in using crowdsourcing to pick up the slack where their budgets end. Click-based museum participation and user-generated online collections metadata enhancement, billed as global engagement, gamify archival labor. The British Library’s Metadata Games project, The Science Museum of London-supported Museum Metadata Games project, and the usertagging projects of The Brooklyn Museum and the Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt Museum, to name a few, ask the public to help describe and categorize the institution’s scanned, digital repositories. Such events offer access to institutional resources and archives, but also inaugurate museum audiences into a database-driven, pedagogical arts economy.

USER GENERATED TASTE

“Software is eating the world”, Marc Andreessen famously said. Venkatesh Rao put it, "Software can increasingly go wherever writing and money can go, and beyond. Software can also eat both, and take them to places they cannot go on their own." Software has also eaten cultural industries; from the way art is bought and sold, to the way that it is discovered.

The Artsy Art Genome Project, claimed by founder Carter Cleveland to be the “Pandora for fine art,” presents a corporate form of metadata as ideology. Artsy’s metadata tags for artworks are called genes–binary-conforming traits like “childhood,” “reclining,” “eye contact,” or “venus,” a weird, datafied Aby Warburg Institute of the present. Is the Art Genome Project, the metadata search technology behind Artsy, a democratizing force or just a floodgate for its target, new-money clientele, eager to gain some quick cultural capital by purchasing art? Critic Mike Pepi’s class-cum-philosophical practice Cloud Based Institutional Critique has developed a line of critique of the networked digital institution in a series of coordinated discussions.

Mike Pepi notes in an email to the author,

What is sold as access to the art world is a really a digital land grab, and exercise in SEO so that new entrants to the art markets will be brokered through their platform. It is an exercise in centralization attempted previously by Artnet and auction houses, just this time couched in the rhetoric of openness and breaking down walls via the web. They are among the first art concerns to recognize that the real judge to please are search algorithms. This is only meant to grow the 60 Billion per annum art market, and capture that value via a yet-to-be configured mechanism.

What Pepi brings to our attention is a digital “land grab,” which serves the purpose of enacting institutional strategies for maintaining relevance that pre-dated the internet, but that uses data / metadata as ideology.

While Artsy is no museum, it bears the ever-constant threat of the corporate art world subsuming the roles of the institution, in this case generating metadata that might bring it to the top of a Google search for “Frank Lloyd Wright” over the territorial Frank Lloyd Wright institutional heirs like the Guggenheim Museum.

INSTAGRAM POPULISM

Where once Cindy Sherman’s parody of the centerfold-girl made art headlines, today the artist parodying the sugarbaby is a routine cost of admissions to art world “discovery,” whether that means being re-photographed by Deviant Art world fan-art exploiters, like Richard Prince; given a database page on 89Plus; or being written about for your ironic sexiness in Vice magazine. The trouble is the parodying of the banal, however novel it was in the Pictures Show generation, is now so utterly banal and expectable that former Disney child star Shia Labeouf watching his own films at the Angelika theater for Performa as “performance art,” can hardly get a serious critic to take notice. Had this been the 1980s, an MIT Press art journal would have devoted an issue to debating the importance of such a gesture.

Where once Cindy Sherman’s parody of the centerfold-girl made art headlines, today the artist parodying the sugarbaby is a routine cost of admissions to art world “discovery,” whether that means being re-photographed by Deviant Art world fan-art exploiters, like Richard Prince; given a database page on 89Plus; or being written about for your ironic sexiness in Vice magazine. The trouble is the parodying of the banal, however novel it was in the Pictures Show generation, is now so utterly banal and expectable that former Disney child star Shia Labeouf watching his own films at the Angelika theater for Performa as “performance art,” can hardly get a serious critic to take notice. Had this been the 1980s, an MIT Press art journal would have devoted an issue to debating the importance of such a gesture.

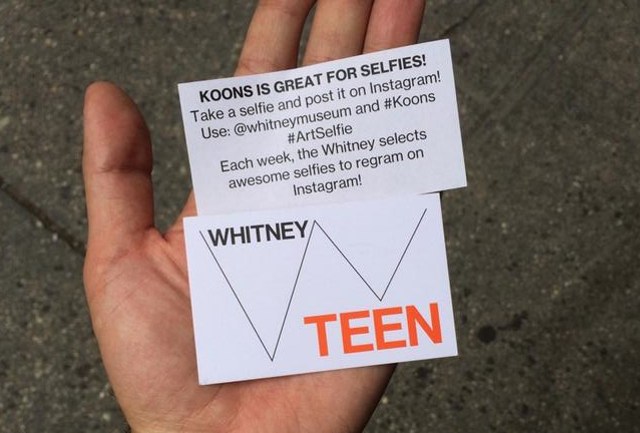

To the new international youth audience of art, the Instagram-ready, ironically hot woman artist is an addictive and important entryway into the contemporary museum. Following suit, museums employ gypset (gypsy-jet set) social media excerpts like the Guggenheim’s Director of Digital Marketing and Instagram starlet Jia Jia Fei and other experts of the #artselfie. The #artselfie, as seen in DIS’s new #artselfie publication, takes ironic portraiture to its corporate extreme. “Koons is Great for Selfies,” declared the Whitney Museum on their Koons tickets. Artists can hardly avoid the question of how social media affects their art, and for some, the social media stage upon which artwork is socialized and reacted to, takes precedent over objects themselves. The rise of the selfie can be seen dialectically as a way to counter (at least at “face” value) the historical avant-garde’s elitism, and celebrate goofy, cute, quotidian humanity.

FESTIVITIES

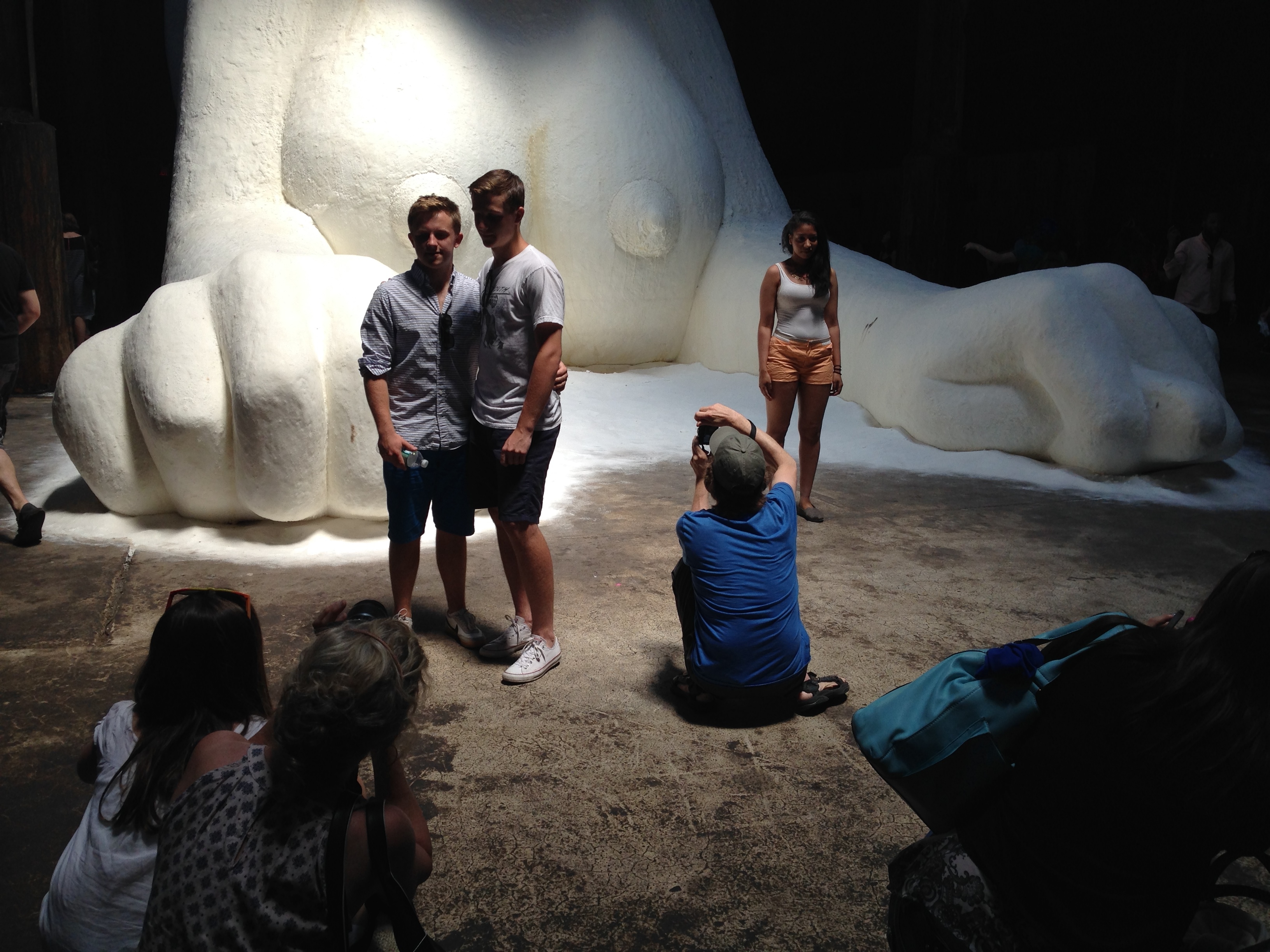

Kara Walker, “A Subtlety,” Domino Sugar Factory, New York. Spring, 2014.

The recent rise of big parties for museums including teen nights, sleepovers, block parties, and music festivals (sometimes sponsored by luxury vodka brands) serve to appease state funding and mask the role of large-property owning museums in real estate gentrification. To bolster this move, formally dissonant art that might expose or call-out the structural/property gentrification must be excised. Even if the general punk attitude of such evenings is “fuck gentrification.”

However, the old guard of institutional critique remains a staple, albeit not a summer favorite. Then there are the token bad boys who get a general free pass, Richard Prince, Thomas Hirschhorn, the YBAs. But it’s all in framing. For instance, the Whitney installs the Jeff Koons show as a gesture of accessibility in a way that lacks ironic cunning but is rather bureaucratically banal, and completely hides any of the charges of sexist, racist, classist, elitism that regularly comes up in reviews of his shows.

Perhaps the most daring complication of the banality of bureaucratic framings is Kara Walker, who recently installed security cameras to record the voyeuristic tourism and blatant exhibitionism of selfie-taking art-goers at her 2014 installation “A Subtlety.” In contrast, Damien Hirst, and Richard Prince have never really risen above a sophomoric obsession with recycling misogynistic concepts from the Modernist avant-garde. Not coincidentally, they have therefore received praise from third-generation “avant-garde” critics who cling to Frankfurt School orthodoxy, though the Guardian has lamented the loss of 'shock value' art in museums.

On the other hand, as the Western museum structure increases in visibility and global power, it also increasingly comes under attack. Michelle Obama offered at the dedication of the new Whitney Museum of American Art (April 30, 2015): “There are so many kids in this country who look at places like museums and concert halls and other cultural centers, and they think to themselves, ‘Well, that’s not a place for me — for someone who looks like me, for someone who comes from my neighborhood.’” And there’s always the potential for smart infographics and critique for museum’s elitist, racist, classist, sexist practices to go viral. But the museum’s sneak rebuttal is absorption (for instance, the Guerrilla Girls are now doing an event at the MoMA bookstore selling tschackas), and festivity—neither of which changes or unmasks the private structure of the museum.

The festivities themselves can and do often contain an edge and free-spiritedness on behalf of the artists (and sometimes the curators) that is creatively adventurous, and exciting. On the other hand, though, there is sometimes a danger of museumification becoming a kind of mummification, not just of the artist, but also of the culture—without spaces in New York for unglamorous experimentation and residency the development of the performer and their audience can become totally halted. The 80s Club Kid sensibility hitches a ride directly into the museum (before it even “experiments” anywhere else). Such silliness led 80s diva Grace Jones’ quip that queer pop performers today are not only copycats but more importantly, conceptually and aesthetically, “middle of the road.” A point that ought as well to be applied to “queer-friendly” publications like Vice Magazine, which function merely as the new New Yorker, which provide a brisk encapsulation of what is “hip” for the lay spectator.

Moreover, the appropriation of “nihilistic” New York culture, particularly in the MoMA PS1 party dome, such as the Semiotext(e) festivities, or the triple canonizations (or cannibalization) of Diamanda Galas and Genesis P-Orridge, or even the annual New York Art Book Fair counterculture zine-frenzy seem always ill-fitted to the space they are rendered within. After all, Galas once said she wanted nobody to dance at her shows.

The idea of having a club or punk culture rise and fall only within the museum is creatively paradoxical, though it can, at times, be aesthetically interesting. Though, most who attend these festivities will remark at the homogenous nature of the dancing crowds, who share in ambiguous politics but a Marxist / anarchic hipster dress code. Places where you can be whoever you want to be, as long as that lines up with what everyone else is being. And you can be new and innovative, as long as it lines up with the latest season in fashion. It is a new way for everyone to get fifteen minutes of inclusion.

And yet we cannot trace the nouveau riche “block party” phenomenon to Warhol, who was too far “outside” of politics to be communally located, but also too “inside” aesthetic aristocracy to be celebrated as an outsider. Rather, Keith Haring, as the Phoenix borne from Warhol’s ashes, signifies the rise of the gay male foundation system, and the selling of the specific mourning of gay identity politics in the sweet colors of un-ironically appropriated hip-hop and graffiti imagery. And most famously, from his “pop shop,” we get the ready-to-wear versions of museum art that the layperson can wear (be it a condom, a vodka bottle, or a sweater).

Flagrant museum corporatism vis-à-vis an academically socio-political standpoint is a very nice way to complicate high/low art boundaries, and allow a wider range of cultural practices into the museum, including the sensibility of “complicity” and “femininity” that is not as staunchly Marxist or avant-garde in a sense that can rightly be conflated with masculinism and old money. However, if one starts to view it from the perspective of cash, it becomes clear that this move appeases the public, the donors, and the state, at the expense of putting forward art that might be formally disjunctive and unpopular.

In fact, a good case has yet to be made in recent years for “unpopular” art, as most art criticism tries to sell art from the perspective of the historical lineage of aestheticism and academic criticism, or from the vantage point of political applicability to everyday life and everyday emotions. So the elite academy and ordinary life remain a constant dualism in the preparation of art—simply because no matter how populist a museum might be, the museum is an inherently anti-populist space—it does not and cannot give a slot to everybody and fundamentally has zero use value, as regards the “care” of the human population.

FASHION-AS-ART-AS-EDUCATION

This all becomes rather pricklier when fashion itself is the object the museum places in its display case. Either history is used to couch the objects as “not art but artifact,” (standard practice with reprehensible images of atrocity and/or propaganda), or theory is used to couch the objects as guilt-free “aesthetic treasures.” For instance, The Metropolitan Museum used theories of cross-cultural orientalist complicity for their recent show, China: Through The Looking Glass. While, in their 2013 exhibition PUNK: Chaos to Couture, “costumes” were displayed as relics of anarchist street culture, while also pointing to their near instant fetishization in high fashion with the change of a mere room—the first being filthy bathrooms from a punk club, the next a pristine runway.

The Met’s fashion institute is trapped in the between abject grime and aristocratic importance (the sacred and the profane), and the decadent artists they privilege seem to mirror this trap—Vivienne Westwood, openly wants her clothes to be considered specialties for the rich, and Alexander McQueen, whose “melancholic” solipsistic romanticism nonetheless always coincided with the needs of fashion week.

On the flipside, the gallery valorization of underground fashion singles out artists who fervently protested the machinations of the market to determine value, such as Jack Smith. As such, Barbara Gladstone’s privatization of his collection into the hands of rich buyers is a dysphoric move, whereas the Met’s showcasing of McQueen and Westwood is fitting.

The biggest fashion-as-art folly in recent memory was The Rise of Sneaker Culture at the Brooklyn Museum. Unsurprisingly, given the corporate (Nike) sponsorship, sweatshop labor is not mentioned, even as an apologia, whereas the Met, at least, nodded to Edward Said in their China show, before negating him. The show seemed to assume viewers wouldn’t do a routine Google search on the presented materials, a search that would reveal a knot of contradictions that no “professional” critic would need to deconstruct.

Due to the glaring absence of the words “sweatshop” or “labor,” the show can repeatedly claim that “women” have little to nothing to do with the production, design, and wearing of sneakers, as if caught in the snag of their own deceit. From a caption:

Female interest in sneaker culture has largely been redirected to shoes that refer to sneakers and yet aren’t the real thing, like the wedge sneaker. This shoe is a part of a larger continuum of footwear made for women, dating back to the 1920s that flirts with, but doesn’t admit, women into the sneaker game.

The language here is tellingly old-fashioned for a show premised on showcasing the populist, community-aesthetic of the “new” consumer-driven aesthetics. The “real thing” is the phallic sneaker, which the woman is denied.

Compounding the conservative values of this “liberal” show is the fact that a floor below is Zanele Muholi’s show Isibonelo/Evidence, 87 photographs from the “Faces and Phases” project Muholi started in 2006 and exhibited at Documenta 13 in Kassel, which could be described as curatorially opposite in its introspection and density. Muholi’s bio labels her as journalist and activist, rather than artist, and the show depicts close-up face photographs of LGBTQ persons in South Africa, a mural of quotations from the subjects, and a timeline of the abuses they have faced.

The curatorial fear would be of presenting spectacle and not documentary, that the photos might be read as more important than the people, and the artist and the museum might take precedence over the shows educational-political message. This fear is reasonable, given that the show directly upstairs is an apolitical celebration of corporate culture—and people coming from that blockbuster show are likely to only stumble upon these important photographs.

Since the sneaker show makes the “real thing” into a phallic sneaker, it’s hard to equate that definition of the “real,” with the humanistic and politicized definition of the real in the Muholi show (Real qua face-of-the-Other).As different as the two Brooklyn Museum shows may be, they beg the same curatorial question—why are these objects in a museum and not National Geographic, the Smithsonian, or a Sports Hall of Fame Museum in Hollywood. Are the shows educational, archival, or aesthetic? If it is Muholi’s craft as an artist that counts (her use of angles, colors, framings), then why is that not accounted for?

Why is there no accounting for the labor that builds the shoes? The Marxist answer is that the fetishized commodity is alienated from the human labor that constructed it. Since this theory is well known in curatorial departments, how is its absence justified? Maybe, curators have simply moved beyond any and all needs for justification? Inclusivity, populism, and the institutional critique brand are justification enough.

These tensions are encapsulated in the placement of street graffiti behind museum-sanctioned glass—inaugurating the visitor into the profound tension between the desire to touch & be included in the museum, and the simultaneous criminalization of that desire.

There is always the fear the public will take advantage of the museum’s ever new overtures to new audiences. Within a month of opening, the Met rescinded the right to scrawl graffiti on the Styrofoam walls at their punk show. Evidently, some visitors took things too far. But the real trouble is that visitors didn’t take things far enough. These populist strategies reveal tendencies towards the ongoing aestheticization of community in contemporary institutions. When your counter-cultural zaniness is enlisted to serve a corporate sponsored “non-profit” that claims to be educative, communal, historical, diverse, fun, hip, youthful, liberal, edgy, and commercial—the contradictions are insurmountable. Which is only to say that cultural critique and consumer outreach are uneasy bedfellows. The books are cooked against spontaneity. Hypocrisy and folly may be the only option for that those who want to engage in the contemporary art market. It’s an embarrassing but occasionally satisfying pursuit