Prison Obscura: Inverting the Inversion to Stand Upright

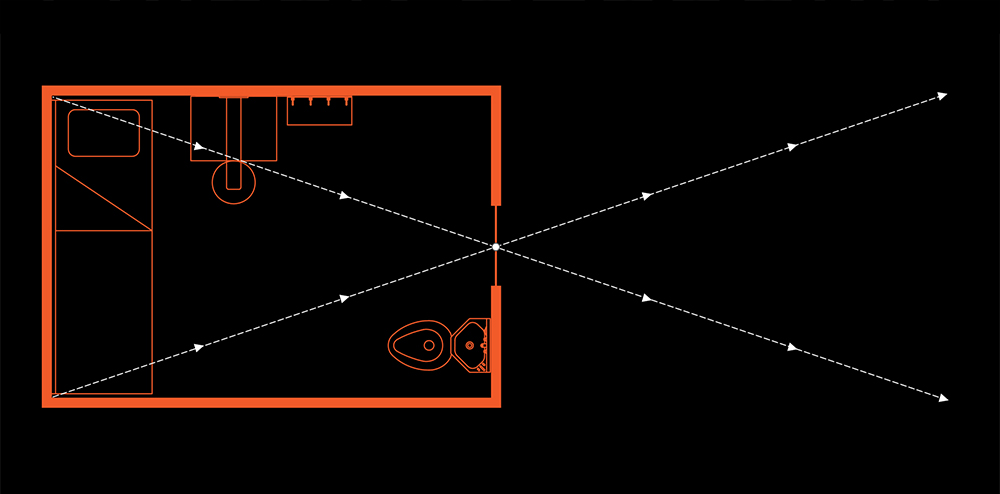

Camera Obscura means “dark chamber.” A precursor to photography, it is a device that allows light to enter through a pinhole that then projects the outside image onto an opposing internal surface so that it can be traced or captured by a light-sensitive material and preserved. Without mirrors, the image projected is always inverted.

The prison is a dark chamber. Ubiquitous but hidden, it is a device that allows light from the outside to enter only through pinholes. It captures, freezes, and preserves. On the walls, shadows are traced that mark time and memory. Without mirrors, the image is an inverted reflection of the light outside.

Prison Obscura, curated by Prison Photography editor Peter Brook, is an exhibit about dark chambers and the relationship of the prison to the camera. Artists explore the dynamic between inside and outside, emancipation and incarceration, light and dark, visibility and invisibility, uprightness and inversion. The camera peers into those dark chambers, not merely as a passive receptor of light, but as an illuminating beacon. The camera does not simply capture these subjects and render them objects (which is the function of the prison), but through propagating these inverted objects, allows others to see/hear/feel, perhaps rendering these objects a standing, a subjectivity, helping them, however incrementally, to express their voice, their dignity, their life.

These are not simply photographs of prisoners and prisons. Indeed, there already are many “images” of the criminal and the prison propagated by popular media: the mugshot, the prison drama, the case study. How we “see” the incarcerated is something shaped by the camera through a sensationalized lens. These images, however, amount to forms of voyeurism, rendering such “criminals” even more objectified and passive. Ultimately, they are propaganda, either inciting fear or developing an entertaining caricature that, in the end, does not reflect reality, but remains only an inverted and blurred obscurity that deflects any meaningful reflection, personal or societal, on the horror that is the U.S. penal system.

Prison Obscura seeks to invert the inversion and negate the negative. By pulling us between this dialectic of subject and object, face-to-face and interface, concrete (and razor wire) and abstract, the exhibit presents a more complete “picture” of the prison and those human beings inside.

In “Take a Picture, Tell a Story”, Robert Gumpert seeks to emancipate the image from its inherent object nature by coupling photo with voice. The photos are striking—“high-contrast, black and white, scars and gripping gazes”—but alone they run the risk of simply perpetuating or glorifying the popular image of “the criminal.” When we hear the accompanying stories, the images are not only lifted out of their flatness, they become human. Joan Didion famously quips, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” A central part of having an identity is having a narrative, a “story.” From this story-telling—not only to ourselves, but to others—we make sense of the scattered pieces, constructing a unity from the fragments, and through this creative assembly, not only an identity emerges, but a “life.”

As another way to “restore some level of empowerment…and to balance the equation between the convicted person and the camera lens,” Kristen S. Wilkens’ “Supplication” presents diptychs of incarcerated women alongside photographs of sites they miss—“sunrises, past homes, mountains, kittens, graves.”

A response to the typical representation of criminals through mugshots, which “are meant to document a transgressor, but act to criminalize individuals and strip them of identity and sympathy,” we see the women choosing their pose, often smiling, reclaiming a piece of dignity and a sense of place by literally standing next to their memories and longings.

We move from the fine-grained analog faces of Gumpert and Wilkens to the interface of pixelated digital satellite images. Josh Begley’s “Prison Map” is a literal view from space. He collects aerial views of “every carceral facility in the U.S.”, some 5,000, from Google Maps. This twisted tapestry makes apparent not only the similarities in architecture, structures designed to maximize control and surveillance, but gives a “picture” of the size of the Leviathan, a creature whose tentacles extend across the landscape, that nourishes itself on the lives of these “criminals”—the organelle of the body inside the cells of the prisons that make up the organs of the behemoth.

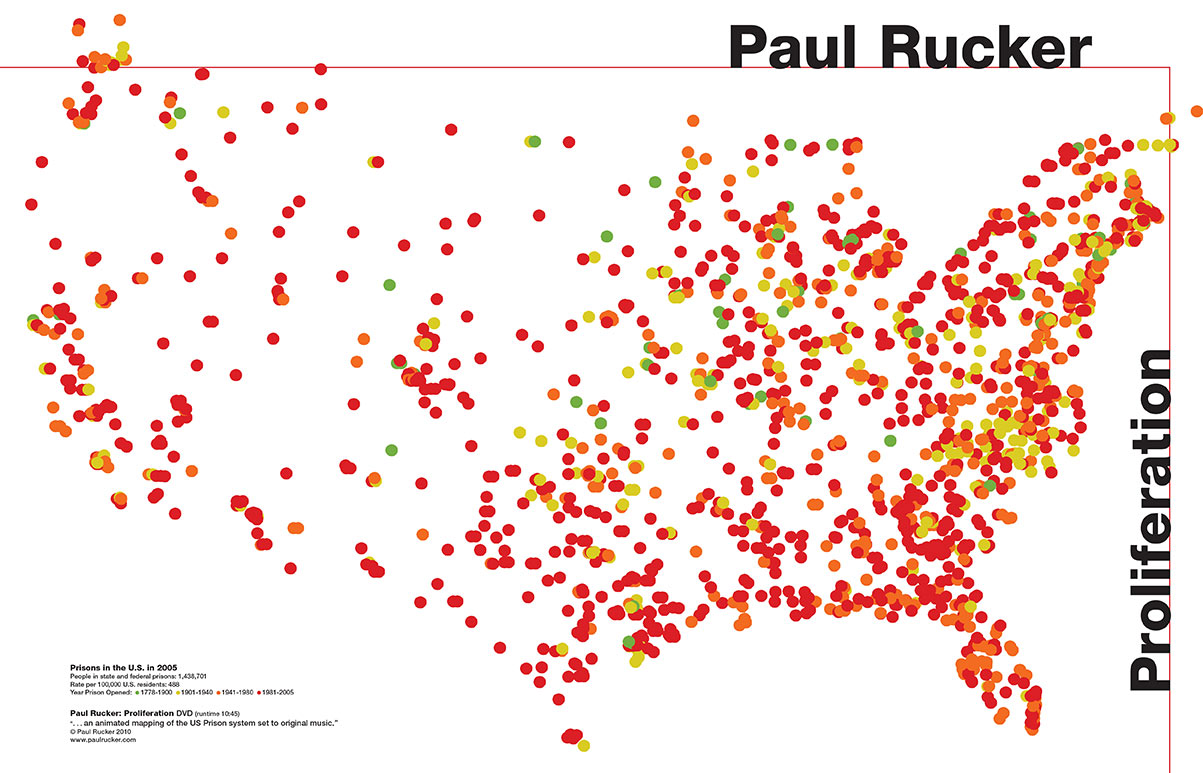

Relatedly, Paul Rucker’s “Proliferation” is an animated video of a map that “compresses 250 years of American prison construction into 10 minutes.” The “picture” of incarceration now moves across time, and we see the “Big Bang” that has created these worlds. Perhaps the better metaphor is not of a “Big Bang” or a “Leviathan,” but one of disease, each dot a pox of a plague on all our houses, propagating, infecting. By condensing time, we see how the prison is a recent phenomenon in the history of human society. More critically, we see how the history of the prison runs parallel to the history of the U.S., a country so proud of being a “beacon of democracy”, a “City upon a Hill.” But where does this beacon’s light shine? Who do the cities on the peak look down upon in the valleys?

“Brown v. Plata/Brown v. Coleman” takes the abstract information of a court case and turns it into a picture of human suffering. Both cases were class action lawsuits against the governor of California on how medical and mental health services in California prisons violated the Eighth Amendment, the Constitutional guarantor against cruel and unusual punishment. The exhibit is simply a collection of images and documents used in the case, but when placed altogether—side-by-side, stacked on top of each other—we get a sense of the claustrophobic and inhumane fact of being in an overcrowded prison. Whether in a holding cage or packed into bunkbeds three-high, such crowding is the opposite of the inhumanity of solitary confinement—no private space, no retreat, humans stacked on top of each other like the galley of a slave ship or a mass grave.

The ruling “transferred health care into the hands of federal receivership…[and] instructed that 32,000 prisoners should be moved from state prison to elsewhere.” Protesters derided Justice Kennedy (appointed by Ronald Reagan) who included three of these photos in the appendix of the ruling, claiming the photos were “too imprecise and emotional to have any place in a high profile legal case.” Such is the unsettling power of the photo. Such is the danger of writing with light.

In “Prison Landscape”, Alyse Emdur photographs visiting-room backdrops, painted scenes where the incarcerated take photos with friends and family. They are like plywood cutouts in theme parks, depicting idyllic scenes of the country or the city in simple bright colors, places of fantasy only existing in the imagination, not actual experience. A conscious effort is made to ensure that there is no evidence that this photo was taken in a prison—no doors, no cells, no surveillance cameras. By emphasizing this background that is an attempt to turn the fact of the wall into a trompe l’oeil of freedom, Emdur’s photos foreground the illusion, exposing it for the charade that it is.

One of the most precious and upsetting works is Mark Strandquist’s “Some Other Places We’ve Missed.” Strandquist asks prisoners a simple question: “If you had a window in your cell, what place from your past would it look out onto?” He then would try to render the fantasy into a photograph from something outside. Pocahontas Dam: “As I stare out of my window through the bars I can see The Dam…Our names mark the rocks…The Dam is always flowing no matter what happens…It never judges me and will always be there to welcome me back.” A hall: “My sister and I running halfway down the hallway and sliding the remaining of the way in our socks….This hallway is filled with much laughter and fun. No worries. I miss this place.” A street corner: “Take a picture of 27th Street street sign. This spot was special to me because it will always remind me if I continue living the street life I will be jail [sic.], institution, death.” The camera: a proxy for eyes and memory, but also hope and regret. The photographer: a messenger that delivers light into and from the dark chamber.

The camera, or any image, renders “reality” unreal, out of time and place. It turns subjects into objects, autonomies into heteronomies, freedoms into incarcerations. There is some truth to the belief of some indigenous people that the photo is a technology that steals souls.

But the photograph can also transubstantiate. Through this encounter of the subject that is in the object (the photograph), the object can transcend its objectivity and become a new subject. A certain dignity and voice become manifest because another subject sees them, recognizes them. In this way, the camera becomes more than a mechanical eye, passive and voyeuristic, but a metonymy for all human senses. We see the prisoner, but we also hear her voice and relate to her trauma. Through the photo, the prisoner becomes less like an alien other, an incomprehensible “monster,” and more like us, a living thing. The experience of this relation is a necessary precondition for empathy, and it is precisely through this relation that we come to experience our own selves as “free.” Is not crime itself often precisely this failure of empathy, perhaps on the part of the criminal, but just as much on the part of society’s members? Rather than continue to exclude, marginalize, exile, and throw into the dark, something that has obviously exacerbated this problem, might the question of crime and the prison be more adequately and humanely addressed by windows than walls? If we look away from the incarcerated, do we not potentially imprison our selves?

To those outside of the prison, it is a dark chamber, a camera obscura. To those inside, it is all light and there are few places to hide. The irony is that in this heart of darkness, they are most visible, always watched. Like photographs, the prisoners are captured, inverted, rendered silent, frozen in time and place, but never developed. Light is not allowed in, nor is it allowed out. It is a black hole that has become a closed system.

The images of Prison Obscura attempt to create an aperture between prison and society, reminding that those trapped inside do retain a voice, a face, a time, a place. Through the process of objectification that is photography, a subjectivity emerges, an identity, a recognition, not only the identity of the prisoner, but the identity of the viewer. The negative is negated, and from this, a possible positivity. It is an inversion of the inversion, which perhaps leads to some semblance of standing upright.

Prison Obscura is on view at the Anna-Maria and Stephen Keller Gallery, Sheila C. Johnson Design Center (13th St. and 5th Ave.) through April 17th. Open daily 12:00-6:00pm, Thursday evenings until 8:00pm. Free.