Killing Time, Pt. [8] - Putting Idle Hands To Work

{category_name}

It is possible, however, that the disappearance of the commodity is not a material disappearance, but its visible subordination to the quality of labor behind it. In this sense, the commodity does not disappear as such; it rather becomes increasingly ephemeral, its duration becomes compressed, it becomes more of a process than a finished product. – Tiziana Terranova

To understand how capitalism can put those hands to work, we must look to total activity on the internet, in all of its banalities and innovations. Chatting, blogging, liking, sharing, networking, gaming, buying, selling, commenting, watching, Yelping, tweeting, browsing… many of these activities are profitable (for some) but not directly compensated (for most). It is important to note a distinction that Terranova works to establish between the New Economy, “a historical period marker [that] acknowledges its conventional associations with Internet companies,’ and the digital economy – a less transient phenomenon based on key features of digitized information (its ease of copying and low or zero cost of sharing).”

For Terranova, free labor marks a “moment where this knowledgeable consumption of culture is translated into excess productive activities that are pleasurably embraced and at the same time often shamelessly exploited.” Still, free labor is anything but, and carries with it a number of issues for capitalism. Knowledge is essentially a Concept, an Idea, and notoriously difficult to manage. As such, it becomes a vital experimentation zone for valorizing “forms of labor we do not immediately recognize as such.” Why do people do these things? What are they doing when they do them? Why does it matter, and to whom? These are certainly recreational activities and ways of spending free time; they are also entertaining, social, and affective. Certain cultural forms, it should be cautioned, are never outside but “always and already capitalism,” developed within and for the system until these forms eventually can be realized and channeled seamlessly into the capitalist’s coffers.

This allows for Terranova’s “knowledge class” – the online workers, prominent in the fields of blogging, journalism, programming, activism, graphic design and multimedia, that constitute a strong deposit of political energy. These workers are, for the most part, definitely compensated; some probably over-compensated; many, at the top, hyper-compensated. Knowledge work, though, is different than immaterial labor (primarily because it is paid), and Terranova adheres to a division of immaterial labor into two aspects: the shift in actual labor processes [1] and the so-called cultural facet of the quality of labor. The 24/7 news cycle is denigrated with ease, but little fuss is made about the perpetual deluge of smart take online criticism, as every writer searches for the perfect angle, that unturned stone.

Immaterial labor isn’t isolated to a class, necessarily, nor specific to highly skilled digital laborers, but exists broadly within any post-industrial dominant capitalist society. The capacity to perform this kind of digitized, computerized labor is readily available in the youthful, unemployable worker – the intern. Terranova also interestingly codes immaterial labor as a right, “a virtuality (an undetermined capacity) which belongs to the post-industrial productive subjectivity as a whole.” Everyone can do this kind of work. [2] You are a manager of your self, your activity. This coincides with one of the newer, compelling theoretical area of capitalist critique - slowing down and sleeping more.

Immaterial labor is imbued in the social body to varying degrees of intensity. There is considerable libidinal investment in the personal associations that typify the (activity on the) internet. Participatory internet production is imbued in particular with affect and desire. The objectification and alienation involved in such labor is obscured, potentially non-existent in some cases, because they are designed to be shared from the start, for pleasure, never for pay. [3] This content makes up a bulk of the Internet. Terranova: “Labors of love,” like fan fiction, blogging, image boards and chat rooms, “[do] not exists as a [part of a] free-floating postindustrial utopia but in full, mutually constituting interaction with late capitalism.” How can something I made for fun to share with friends be alienated from me?

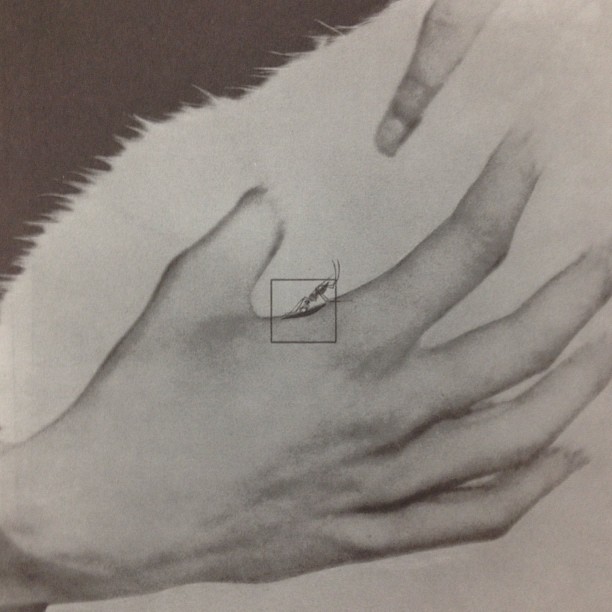

Knowledge is a curious thing to quantify; hence the knowledge worker becomes a problematic class to qualify. Knowledge first became central to labor in the form of skilled handicraft. As factory mechanization attained its primary place in industrial capitalist production, the knowing how (to work machines) began to qualitatively shift labor towards a general intellect where knowledge becomes incarnate within a system of machinery. A touch screen is evocative specimen of that work between. [4] There still remains a void, a problem yet to be solved, in which machines as cannot be deposited into machines in the same form, to the same end, or with the same productive results that it does in humans in humans, to the same end in humans, or produce the same results that it does in humans. Some part of that knowledge comes into being in the machine via the immediate interaction of the labor force.

Capitalism is freeing the commodity of its material form, if it hasn’t totally already. Online, nothing is a finished product. Non-traditional commodity forms are constantly evolving, updating, changing, fixing, linking, debugging and re-working in an indefinite and interminable process of production. Instagram as a commodity is a tool of affect and therein lies its primary value; the community, hardly its rudimentary technology, is where the money is. [5] Its organically operating community, not necessarily its technology, is of value. This is an altogether new relationship and interaction between labor and time, production and time, and quality and time. No one is suggesting that all commodities have disappeared – simply go to Amazon – but “become more transparent” as a result of the kind of labor behind them.

In the early days of the Internet, barely any mass volunteer labor was compensated – and it did not need to be. Money was not driving the burgeoning community nor fostering its participation. Invention itself pushed forward the technology, drawing from a limitless and willing workforce. The tiny fraction that paid was overcompensated at the hierarchical top in owners and CEOs of web companies. Then the bubble burst, and capitalism learned from it’s mistakes. Back to tangible assets, like real estate. It is even more pronounced today. On the whole, the Internet is maintained by an unfathomable amount of labor (in varying degrees of quantity and quality), done willingly for fun. It is co-operation far from the factory, it is interacting with others. This labor presents itself as intimate and personal; it is domestic, un-alienated, homegrown, yours. Why else would this kind of labor be unrecognizable? Since when is work fun?

Terranova, ultimately and astutely, sees the relationship of labor and capital (immaterial and free labor) as one fundamental to late capitalism that, as it has grown and evolved and become late, has led to a relationship that "is mutually constitutive, entangled and crucially forged during the crisis of Fordism.” Free labor is so real because it manifests itself, through the shrewd maneuvering of capitalist ingenuity, as “a desire of labor”, a desire for labor, that is “immanent to late capitalism - it does not appropriate anything: it nurtures, exploits and exhausts its labor force and its cultural and affective production.”

Slowly but surely we inch closer towards the most evocative juncture of work, play, and value in the late capitalism of the early 21st century. Knowledge is both collective and individual, manifest in the material world of computers and the internet. Knowledge labor “is inherently collective, always the result of a collective and social production of knowledge,” and in the informated sphere of internet capitalism, where labor and employment (for lack of a better word) are rarely equivalent, play has been galvanized into action for capitalism by capitalism, and killing time is the name of the game.

[Notes]

[1] For example, how computer literacy/competency is of increasing centrality to labor.

[2] Immaterial labor is not a completely new phenomenon. Variations of “labor not recognized as such” exist in the past as well, most notably in the form of domestic and reproductive labor performed by women. For example, the reproductive labor in a 19th century family necessary to produce a population of new factory workers. Many have drawn on that kind of work to help craft the foundational scholarship that immaterial labor is rooted in. There always has been labor not recognized as such, especially when the unrecognizable labor has its sole referent in the most extreme, physically demanding, and traditional forms of labor. It is difficult to see domestic labor when the industrial factory is blocking the view.

[3] Valorization of these products cannot occur at the command of capital but capital makes sure “to retain control over the unfolding of these literalities and the processes of valorization," says Terranova.

[4] Living, human fingers are the only operators the touch screen responds to. Terranova employs The Matrix to illustrate the “classical” Marxian flesh-and-steel Frankensteinian monster. Post-Marxists theorizing the general intellect later, which opened the door for immaterial and affective labor, did not simply “stop at describing the general intellect as an assemblage of humans and machines at the heat of postindustrial production.” Still, whereas Terranova dismisses that idea, merely an “updated” classical Marxist perspective – “a world-spanning network, where computers use human beings as a way to allow the system of machinery, (and therefore capitalist production) to function” – the internet is in fact a global, connective network. To play up certain phobias as nothing but science-fiction fantasies is to undermine the some of the very real origins of those anxieties in the first place: the Industrial Revolution, the factory, the machine, and the status of the worker and his/her labor in the face of violent and destructive exploitation.

[5] Instagram was purchased by Facebook for $1 billion dollars in a deal that netted the CEO Kevin Systrom $400 million dollars and co-founder Mike Krieger $100 million dollars. Another $100 million dollars was to be paid out among the 13 other employees.

[Works]

Terranova, Tiziana. Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age