Freud’s Ashes

{category_name}I did not grieve for the Professor or think of him. [1]

—H.D.

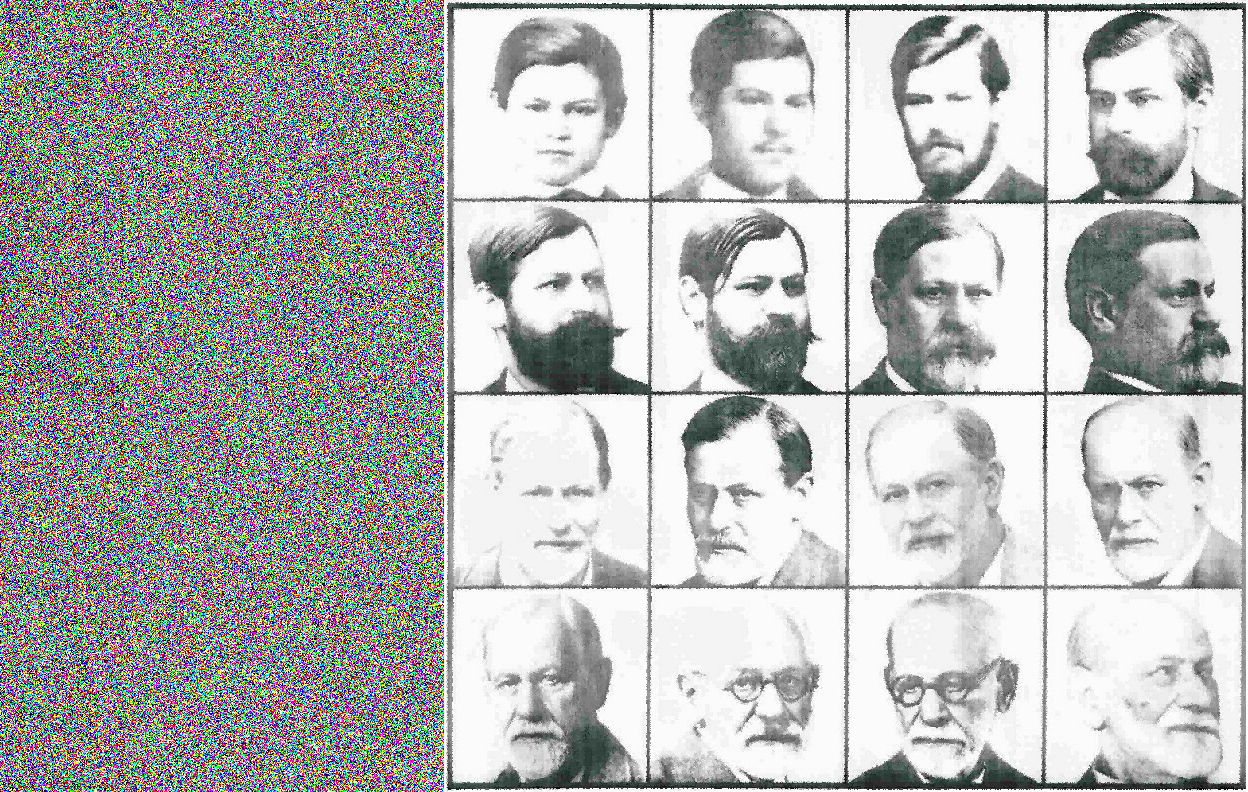

I have been trying to write about Freud for over a year now — ever since I heard about the attempted theft of his ashes. They were in an old Greek urn, given to Freud by the Princess Marie Bonaparte. I imagined the moment that urn crashed in the night. I thought of how it swayed, uncertain of its destiny. I wanted to write about it, about Freud, but I didn’t know what to say.

Instead of writing, I read. I read the pedestal which held the urn. It says:

SIGMVND FREVD

6.5.1856 - 23.9.1939

Below, in smaller type:

MARTHA FREVD

26.7.1861 - 2.11.1951

Their names are carved with the Latin V in place of the U, an engraving convention both forgotten and archaic. Scanning the words — SIGMVND FREVD — generates a tension; I expect a vowel but see a consonant instead. It's a disjuncture of the present, the words comprehensible yet parasitic on the act of reading.

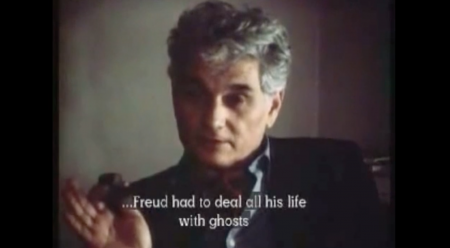

I first learned about Freud through Derrida, sitting in on a course on deconstruction and psychoanalysis. Derrida focused more on Freud’s later writings — the essays on telepathy, Moses and Monotheism, Beyond the Pleasure Principle. He took Freud at his word, and tried to emphasize the consistency in his thought as it had evolved over the years. I liked the peripheral work. I liked the seriousness with which Derrida treated it, too. It’s how I wanted to write.

I read Derrida’s “Freud and the Scene of Writing,” where he talks about Freud’s schema of the mind and how he uses writing not as a metaphor but as a representation. [2] I read “Archive Fever,” an essay about the death drive, the archive, and the aporetic forces of self-destruction and self-preservation. In Derrida’s words: “L’Un se garde de l’autre pour se faire violence.” [3] The unified self is haunted by the forgotten memory of its own fragmentation.

In Derrida’s seminar, The Beast and the Sovereign, he compares forms of burial — cremation versus inhumation. He prefers cremation, in a way, because it is the most paradoxical. You commit a second murder, deprive the dead of a place, and in doing so, you confront a restless and infinite mourning. On this point he quotes Paul Celan: “The world is gone, I must carry you.” [4] Cremation inaugurates the beyond of a corpse, a mourning “infinite and null.” [5] The urn is both a replacement for Freud’s body and a container for his ashes. It is the archive of his second death.

All the passive reading left me feeling paralyzed. I thought of death. I dreamed of Freud’s ghost. I learned that Freud not only decided to be cremated, he also decided when to die. He must have thought of it, although unthinkable. The thought of "living death" brings us closer to the impossible relation to our death, closer to "the zone in which the impossible is named." [6] To venture such thoughts is to pass along the intolerability of dying alive.

I picked up H.D.’s book, Tribute to Freud, about her time in analysis, 1933-34. She said of Freud’s death: “I did not grieve for the Professor or think of him.” [7] She denied mourning. But she also said (perhaps referring to Freud’s impending flight to London) that she wished, and knew, that “the Professor would be born again.” [8] How could she know?

Once Freud died, H.D. did not think of him. Or at least, she didn't think of him in her conscious mind. But the unconscious mind knows not the reality of death. And she of course must have remembered him. Perhaps not often enough, or only in dreams. And she did write of him.

Still I’m trying to write about Freud. But it seems to get harder each time I try. I still can’t shake the image of that urn swaying back and forth in the middle of the night last January. This was before I took that class on psychoanalysis and deconstruction. Before I started going to therapy myself. It was as if the fall of Freud’s urn unfolded a series of events for me. It triggered my renewed interest in him, an interest both intellectual and personal. In the end, is there really a difference?

I stay up late and write about myself as a I write about Freud. I read about H.D. and Freud, Derrida and Freud, Fliess and Freud. There is always more than one. There is no autoanalysis.

I type on my computer. I type on my typewriter. I think about grandiose essays about psychoanalysis, deconstruction, and death. I dream of interweaving my dreams, my autobiography, among these insightful and obscure commentaries. I think about how Freud’s ashes have both destroyed and preserved his body, how he and his wife are indistinguishable in that urn. I want to tell someone, anyone, that I know and understand the nuances of Derrida’s interpretation of psychoanalysis. I understand that the Freudian signature on psychoanalysis is both singular and abyssal. I think of the back and forth of the death knell as Derrida’s figure for fetishism and its contradictory assertions. I dream of saying this all in a way that is both simple and evocative.

I continue to write as the satisfaction with what I have written eludes me. Maybe it will take a lifetime to find that. It may take a lifetime, even after Derrida, to understand and explain the relationship between psychoanalysis, deconstruction, and the history of metaphysics. Maybe it will take a lifetime just to write about this impossibility. Regardless, there was some truth in what H.D. said, about Freud being reborn. H.D. also said, as if continuing the thought: “The dead were living in so far as they lived in memory.” [9] This virtuality inscribed within psychoanalysis inhabits all who speak its name.

There is little to be said that hasn’t been said about Freud. I was overburdened with sourceless fears and imagined counterarguments to my unwritten words. I read another piece by Derrida, this time an address to the States General of Psychoanalysis called “Psychoanalysis Searches the States of Its Soul: The Impossible Beyond of a Sovereign Cruelty.” What I liked most was when he discussed the political stakes of psychoanalysis, and very deliberately used the word “revolution.” He said that the psychoanalytic session can usher in a micro-revolution, “perhaps the first revolution that matters.” [10]

This micro-revolution of self-understanding is with me as I write. It haunts me from the future. I’ve included myself in such a way that seemed inevitable to me. I simply couldn’t resist it. And so it feels like this all has so little do do with Freud. I’ve said so little about him, really. And maybe now I’m coming to a conclusion of sorts. Or at least it feels that way. This whole time I’ve been trying to write of Freud, I’ve also been compelled to write about myself writing. I’ve felt driven to autobiography and resistant to it at the same time.

And this reminds me of what Derrida says when he talks about Freud’s own signature on his archive. There is a connection between psychoanalysis and literature — everything said or written in the name of psychoanalysis is also done in the name of Freud. The science of psychoanalysis is also the science of Freud. This implication of author is the originary complexity of psychoanalysis. It encompasses within itself not just the facts, but the author’s own interpretive struggle. This is why I couldn’t avoid writing about myself, or at least writing about myself writing about Freud. The wager of psychoanalysis is the persistant constructing and unraveling of its most authoritative self. I too have unraveled. I did so in the name of Freud.

Notes

[1] H.D., Tribute to Freud (Boston: New Directions), 12.

[2] Jacques Derrida, Writing and Difference, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 196-231.

[3] Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” trans. Eric Prenowitz, in Diacritics, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Summer, 1995), 51.

[4] Jacques Derrida, The Beast and the Sovereign, Volume II, ed. Michel Lisse, Marie-Louise Mallet, and Ginette Michaud, trans. Geoffrey Bennington (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 176.

[5] Ibid, 169.

[6] Ibid, 148.

[7] H.D., Tribute, 12.

[8] Ibid, 39.

[9] Ibid, 14.

[10] Jacques Derrida, Without Alibi, ed. and trans. Peggy Kamuf (Stanford: Stanford University Press), 253.

Thumbnail image from here with modification by author. Remaining images by Marc Yearsley.