Code on Screen

In many respects, Facebook is the digital banal: it is a daily habit through which life is experienced mediationally. Founded in 2004 by then Harvard student Mark Zuckerberg, along with fellow students Eduardo Saverin, Andrew McCollum, Dustin Moskovitz, and Chris Hughes, Facebook has approximately 1.28 billion users who access the site daily. It was perhaps the first Web 2.0 platform that made the web feel like real life for nonspecialist users. At its inception, Facebook was a site that verified users through their preexisting social networks and replicated those real-world networks exclusively. Since 2004 Facebook has become a default mode of social connection across the globe—85.8 percent of daily active users are outside of the United States and Canada. As Kember and Zylinska argue, “With its constant flow of data, its shaping of human and nonhuman experiences and events, and its reworking of what we understand as a ‘relationship’ and a ‘connection,’ we could perhaps go so far as to suggest that Facebook is a modulation of ‘life itself.’ ” The banality of Facebook in the context of its users’ lives—its everydayness—is both the means by which, and the block to recognizing how, Facebook becomes a modulation of “life itself.” As an interface for social interaction, Facebook works by disappearing; it is a tool for connection. The affective novelty of Facebook is its uncanny re-presentation of your life, but this is effaced and appears instead as efficiency. In practice, Facebook is a program that determines the parameters and quality of “connection” as a reified concept, but in everyday life, it is mostly an icon that users tap to see what their friends and family (and not-so-close connections) are up to. In these ways, Facebook conforms to the operation of the digital banal; the condition by which we don’t notice the affective novelty of becoming-with digital media. In other words, the way we use media makes us unaware of the ways we are co-constituted as subjects with media.

Facebook purports to be a neutral representation of sociality, of its users’ social life. But, as has been consistently reported over the last few years, Facebook is not neutral, just effacing. Facebook’s algorithms are a mode of social design that curates a user’s access to information and communication; moreover, it produces conditions for connection that must be recognized as new affective modes of sociality. Facebook is full of paradoxes: eventalizing the rote and ordinary, connecting without being together, being present in multiplex ways. Users of Facebook are always making their lives visible and present, existing in an unresolved present, where life can be called up and refreshed. This performance of an individual sovereign life, to be witnessed by Facebook and its users as sociality, is also a making over of that life in ever more granular, quantified terms. The banal Facebook paradox is one of storage—the live present of Facebook is possible because data is stored elsewhere. The encounter with live Facebook subjects is possible precisely because subjects are always already interpolated as stored data. Facebook presents an unresolved subject who is becoming-with technology (perpetually in the present), while blocking from view the remaking of the sovereign subject as a software litany (the profiled subject found in directories, routines, archives, history), a neoliberal data subject.

Because Facebook appears as a banal aspect of everyday life, there is a risk of overlooking the profound ways that it is, and is always becoming, life itself. David Fincher’s 2010 film The Social Network, is likely one of the ways we overlook the profound novelty of life lived with digital media. On the surface, it supplies an origin story for Facebook that is determined by what Facebook will have become. It retroactively produces the political conditions of Facebook as it exists today. But, instead of asserting that the historical account offered in The Social Network “tells” us about Facebook, analyzing the film can reveal the ways Facebook is mediationally complex and an ongoing sociopolitical process. The depiction of a Facebook origin story on film also tests the limits of contemporary cinema’s ability to represent its own digital medium, as code appears as yet another discourse of reading and writing. The screen-ness of watching a film about programming is in tension with the narrative work of retrofitting the new normal.

The screen mediates programming code—as the computer monitor—and it is also a site of our cultural mediations about digital life—as cinema. Within studies of digital media, the status of the screen has been challenged: screen-based media studies have dominated critical work on new media, perhaps at the expense of what Matthew G. Kirschenbaum has called the “mechanisms” of digital media. New critical scholarship on media infrastructures also reminds us that digital media is never only an encounter that happens between a human and a screen; it is also data centers, cell towers, undersea cables, and rare-mineral mining, as well as the human, animal, and environmental bodies living, working, and passing through these sites.However, the site of the screen is a problem for narratives of code: what we see on-screen is an abstraction of computational process—no matter how data visualizations might lure us in with the promise of seeing the digital event on screen. If the digital banal is the process by which an encounter with digital media and computation as novel is itself reiterated as to be expected, so that an engagement with the novelty of digital media is affectively obfuscated, then the screen is the first point of (non)entry. Rather than work from an assumption about whether the cinema screen can or cannot enable a way of seeing behind the computer screen, we can attend to the screenness of programming in films, watching the way computer monitors—and the bodies that sit with them, the hackers and programmers—limn the action of code.

In 'The Social Network' the foundational myth of Facebook is narrated as a revenge drama. A young man who is depicted as insensitive and unempathetic to those around him is nonetheless acutely sensitive to the ways he feels slighted in life—by women, by wealth and class and elitism—and sets about righting the obstacles to his proper flourishing by way of an algorithm, which will fix the glitches of human-to-human social networks. In the film the widespread attachment to Facebook is this: you will know if someone is single without even having to ask; you will know who is like you without having to work it out yourself, without having to risk a mistake. The film supplies a story to make sense of the Facebook ideology of connection-as-distance. The film also gives away its own unease with this narrative. It depicts the violence of algorithmically encoding social life, the white male patriarchy of proving the world’s programmability. The Social Network offers a visual grammar of code: a cinema that is attentive to the task of representing code in its material and symbolic state and as an effacing gesture that is also a political reality of everyday life.

Grammars of Code

The Social Network depicts multiple scenes of code writing, particularly hacking, mostly performed by Harvard undergraduates, depicted as geeks in Gap hoodies, drinking light beer and doing shots. In a review of the film, Zadie Smith writes of the dilemma that director David Fincher must have had when deciding whether to include these scenes: “How to convey the pleasure of programming . . . in a way that is both cinematic and comprehensible? Movies are notoriously bad at showing the pleasures and rigors of art-making, even when the medium is familiar. . . . Programming is a whole new kind of problem.” Scenes of programming in The Social Network are not always pleasurable, but they are busy and hyper and engaging. They are also social, not just as the social media network-to-be, but as always-already socially and culturally embedded practices.

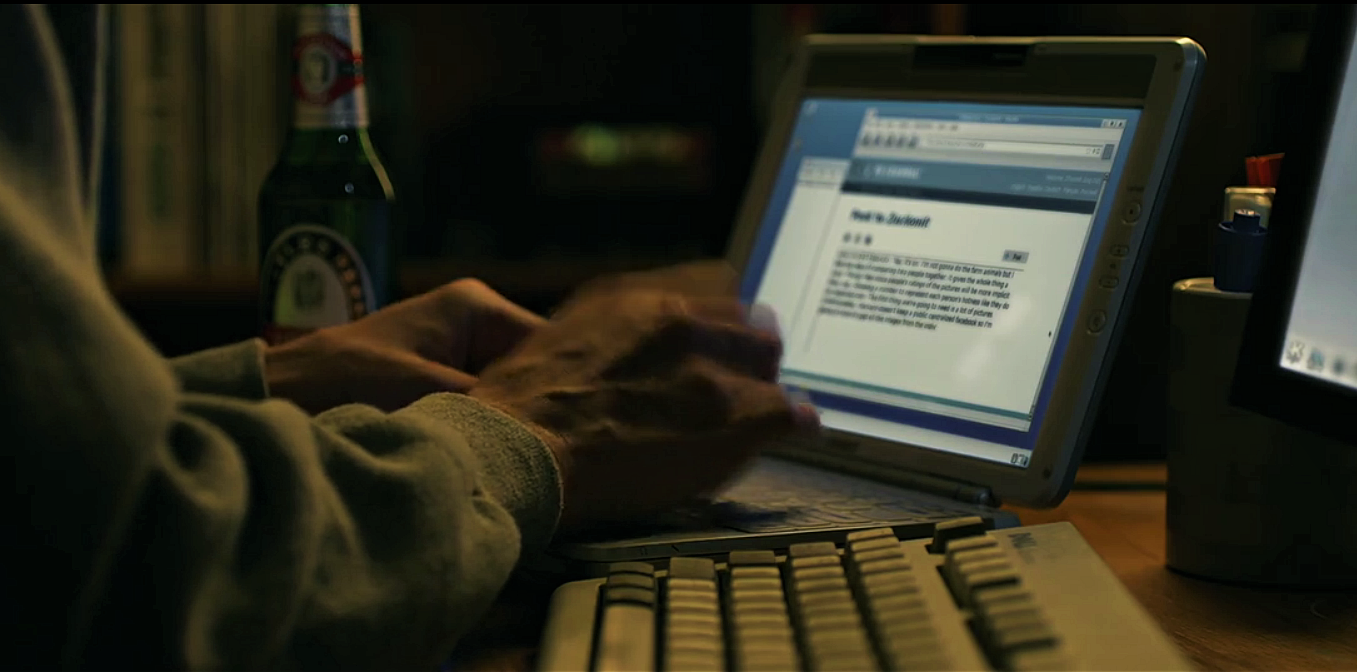

One of the first sequences of the movie shows the character of Mark Zuckerberg (real-life founder of Facebook, played in the film by actor Jesse Eisenberg) arriving home after being dumped by his girlfriend, Erica Albright (Rooney Mara), grabbing a bottle of beer and sitting down to write a blog post about the woman he was just dumped by. This scene takes place at a desktop computer, but the character also has a laptop next to the desktop screen. Open on the laptop is a Harvard website that shows student profiles. Zuckerberg’s roommate jokingly suggests comparing female students’ profiles to pictures of animals and rating them. Zuckerberg decides that rather than compare women’s profiles to animals he should set up a program to rate women’s photos against one another. This thought process is shown on-screen as Zuckerberg types it all in his blog, and it is simultaneously narrated by a voiceover (Eisenberg, playing Zuckerberg, reading the blog aloud). After Zuckerberg has hit on this idea, a quick-cut sequence of programming and blogging commences with his call: “Let the hacking begin.”

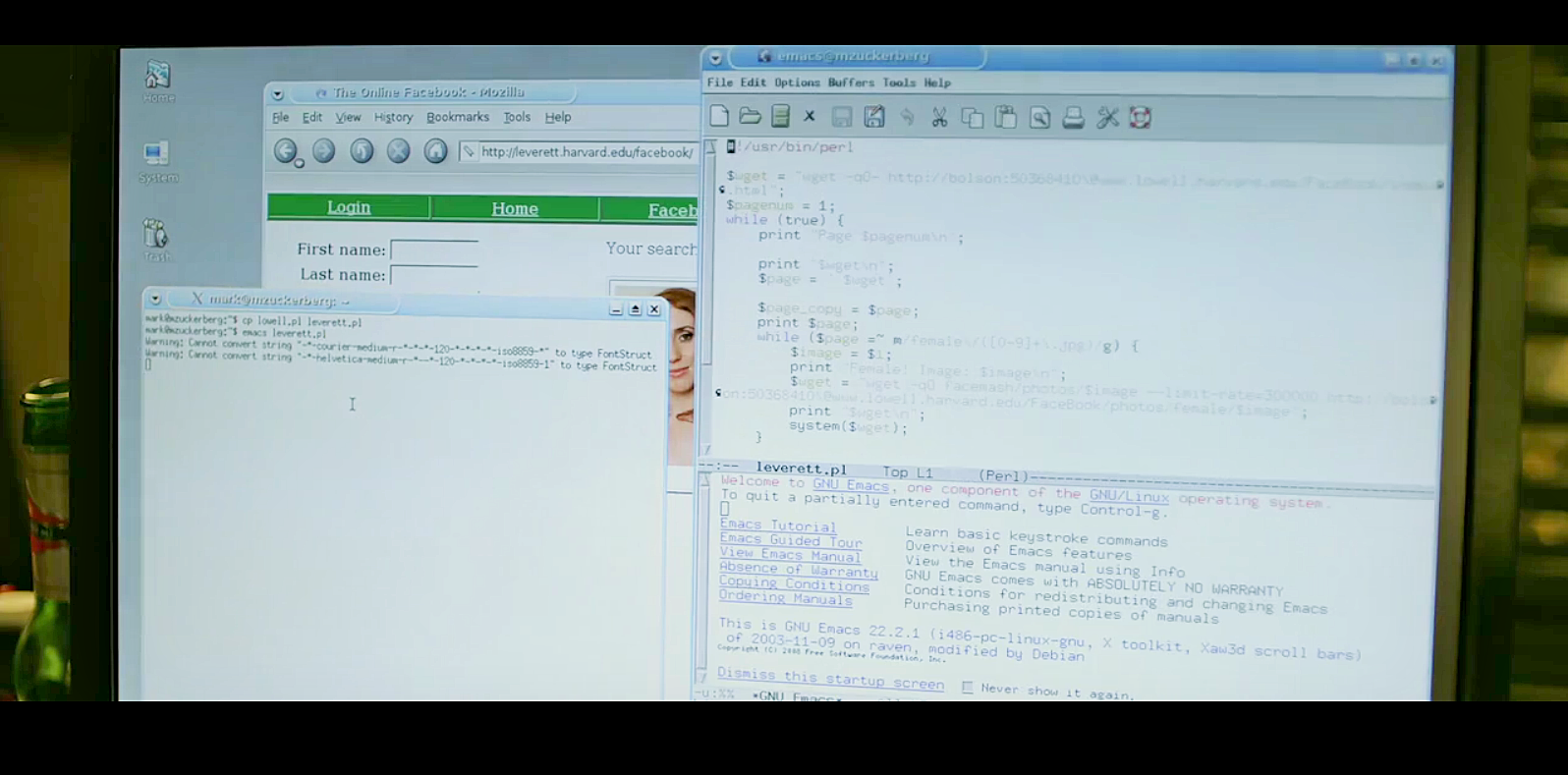

In the scene that follows–the making of Facemash—the voiceover continues to narrate the blog post, which describes the hacking sequence, while on-screen the film alternates between images of the two screens: the blog post and the code for hacking into the Harvard student profile sites. The images of Zuckerberg in his dorm room are spliced with images of action taking place elsewhere on campus: female students arriving at a party in one of the exclusive members’-clubs that Zuckerberg covets. The overall effect of the scene conflates the writing of code with the actions it will eventually effect. Through montage and compressed temporal gestures, Zuckerberg is shown to be literally rewriting the hierarchical nature of social networking (as it is represented by Ivy League institutions). In this sequence, iterability and executability are blurred by the edits of Fincher and his team.

The cuts that switch between the two scenes of action are violent. The women at the frat party are interpolated as data in the program, and this appears as aggressive editorial splicing. While the film offers a fictional origin story for Facebook—Erica Albright—it makes highly visible the exploitation of images of women, which is the Facebook origin story. As Melissa Gira Grant has described it, women “and their representations are [an] intentional . . . part of Facebook”: “the unpaid and underpaid labor of women is essential to making [Facebook] go, to making it so irresistible.” Problematically, despite making this labor visible, the film still skews the historical record of women, particularly Asian American women, who worked at Facebook as programmers and customer service staff in its early incarnation. As Lisa Nakamura highlights, in The Social Network the depiction of “Asian women’s labor as sexual rather than technical obscures rather than exposes the workers of color who ‘make’ social media.”

Alongside the construction of the social network played out in the Facemash scene are contrasting practices of reading and writing, which are represented on-screen as the blog post/voiceover and the programming code. In the scene the depictions of writing flicker between writing plaintext with HTML (for the blog) and writing command code (for Facemash). These are two different languages. Both are higher-level programming languages, but HTML is written in plaintext (natural language) with additional rules that are deployed to dictate the appearance of that text online. The code for Facemash is a structural layer below this (such as C++). The scene is soundtracked by pounding dance music, and within the same long scene (full of short edits) we see the instant “liveness” of Facemash as (mostly male) students in other dorms get sent a link to the site and begin rating the photos. The ellipses between Zuckerberg’s blog text (readable) and his program text (code) serve to give an impression of fluidity to the procedures for writing structural code. The voiceover in this scene explains the procedures of code, framing the visually disconcerting switches between scenes and screens with a smooth technical narrative that performs the disciplinary norms of patriarchy in a manner that seems like algorithmic inevitability. The dialogue in this scene that refers to code is, for the most part, technically authentic—the only changes Mark Zuckerberg requested to be made to the script were those referring to the programs and algorithms he used to build the initial site. The voiceover has the added effect of distinguishing between the two writing procedures, giving human inflection to the blog post, which in turn functions as a way for the viewer to understand what is happening in the representation of code writing.

The code is only named, and therefore technically understood, through the blog: “definitely necessary to break out the Emacs and modify that Perl script.” Its appearance on-screen is not legible—it is depicted as blurry lines of indistinguishable characters. The programming characters are lighter in color than the blog font; viewers are permitted to not know, or even to not see, this operation. In contrast, the blog text as seen on-screen is perfectly legible, and the audience can read along with the voiceover. The scene is fraught with the anxiety of distance between user and code. This anxiety is represented textually through multiple representations of reading, writing, and narrative. The counterpoint to these multiple depictions of reading and writing is one that epitomizes the difficulty in narrativizing code: in this section of The Social Network the blog functions as the narrative frame for that which resists narrative—code. This happens visually (the viewer can read the blog but not the code script) and verbally (the viewers do not necessarily know what “Emacs” or “Perl” refer to, but they can follow the context). And yet, even with such an accessible cinematic frame, this representation does not technically render the code readable or understandable; it merely conflates the difference between seeing and reading, or between viewing and understanding. The production of code in the cultural imaginary as yet another mode of reading and writing is one way in which the executibility of code as machinic discourse is effaced. In the scenes of programming described above, the performance of the programmer is one of sovereignty: the programmer rewrites the world.

Such scenes narrativize code as constitutional. As Chun has written, the executability of code is not law, but rather “every lawyer’s dream of what law should be: automatically enabling and disabling certain actions and functioning at the level of everyday practice.” Here Zuckerberg is seen to be constituting a new social order, and this constitution is depicted as latent with meaning. The programming frenzy we watch on-screen is energized by a dramatization of historical affect that was lacking in the actual historical architecture of Facebook: Zuckerberg was hurting. The hurting leads to the hacking as a distraction (and as revenge), and the hacking involves scrolling through photos of women in Zuckerberg’s social network. In tension with the performance of what could have been—the emotional frenzy—is the banal affect of what has become—our distracted swiping, our protracted userness, our unresolving present, our scrolling through Facebook profiles. In other words, these scenes exemplify the digital banal: they are meant to be exciting and show us the dawn of some new thing, but the excitement and energy is displaced onto and dispersed throughout old things (partying, heartbreak, misogyny), and the means by which the new is being constituted—hacking—appears as just another text in the process of being written. In these early scenes of The Social Network, the audience is presented with a benign avowal of the new order, or, here a violent reordering of the social appears as a same old slice of life itself.

References

Wendy Chun, “Crisis, Crisis, Crisis, or Sovereignty and Networks,” Theory Culture Society 28, no.6 (2011)

Melissa Gira Grant, “Girl Geeks and Boy Kings.” Dissent (Winter 2013)

Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska, Life after New Media: Mediation as a Vital Process. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 2012

Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008.

Lisa Nakamura, “The Comfort Women of the Digital Industries: Asian Women in David Fincher’s The Social Network.” In Media Res. January 17, 2011

Zadie Smith, “Generation Why?” New York Review of Books. November 25, 2010

This essay appears in a different form in the forthcoming book The Digital Banal: New Media and American Literature and Culture (Columbia University Press)